This paper assesses the resources necessary to implement a proposed care pathway for the management of the entire spectrum of spinal disorders which could be used to inform the implementation of a model of care in communities which do not have established spine care programs. This description of resources was developed with the goal of avoiding many of the concerns that have been raised about the provision of spine care in high-income, high-resource countries which have seen a marked increase in the cost of providing care without any evident reduction in spine-related disability [19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. The hope is to avoid the increasing use of high-cost, high-tech passive interventions which have become an increasing component of spine care in high-income countries and which have not been shown to have a major impact on spine-related disability [24]. This article identifies the resources necessary to achieve an evidence-based spine care delivery system which is patient-centered and takes into account the patient and community needs and priorities [25].

There is little information in the peer-reviewed literature that addresses the resources necessary to implement a model of care for the management of spinal disorders. Extensive work has been done in Australia to propose a model of care for musculoskeletal disorders that relies on multidisciplinary teams [26]. However, the authors do not describe the resources necessary to implement the model. It is therefore necessary to visit the literature on resource determination for general health or other specific disease categories when considering the reasonableness of the categories used in this survey.

We have attempted to apply examples from other fields to address the needs in our study. One example of a toolbox comes from the Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas (https://ctb.ku.edu/en). They describe the importance of assessing the needs and resources to improve health care in their communities in the most logical and efficient manner. Their toolbox describes assets that include individuals, organizations and institutions, buildings, landscapes and equipment and is consistent with the survey used in this study.

Other examples include human resources and models of mental healthcare integration into primary and community care in India that may be helpful in providing additional insight. Solutions to address the scarcity of mental healthcare specialists in India included the development of diverse community mental healthcare models, specific to the local context. These models emphasized the importance of community-based primary mental health caregivers who work closely with specialists for the most ill patients. The model provided in the India context has similarities to the model being proposed for spine care [27]. The WHO undertook a survey to assess the capacity of Member States to develop and implement programs that focused on addressing hearing loss. The lack of human, financial and educational resources were identified as significant barriers to implementing programs and policies necessary to address the needs of people with hearing loss [28]. The WHO found that 28% of countries facilitated delivery of hearing programs through collaboration with other government agencies, healthcare groups, funding resources, nongovernmental organizations and professional bodies. Spine care in poorly resourced settings may be similarly aided by sharing of resources or by supplementing existing healthcare facilities, infrastructure, human and funding resources [27, 29].

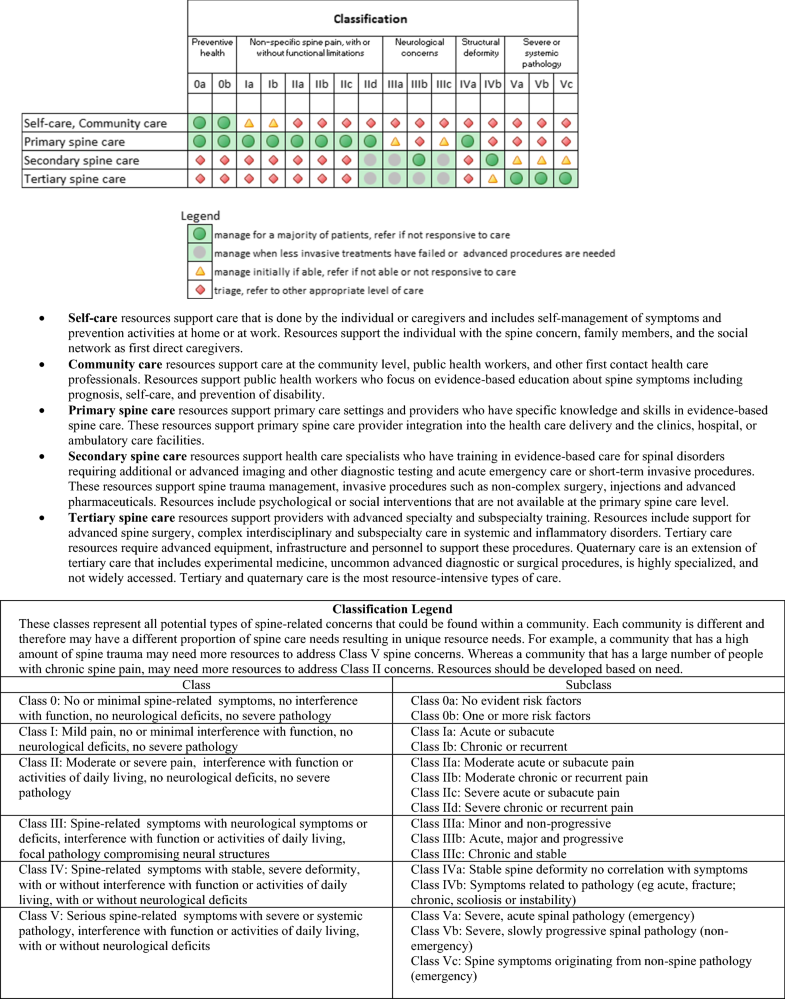

We have proposed four categories of resources to deliver spine care in addition to funding availability. We make the assumption that funding is a critical resource across all settings and do not specifically address it in this manuscript. These resource categories include knowledge and skills, materials and equipment, human resources and facilities and infrastructure. The respondents to the survey in this article clearly articulated that the type of resources required to provide care is dependent on the nature or class of spinal disorders that are to be managed in a specific setting. It is crucial to take into account the resources that are already present in the target community [8]. Based on the resources identified, we developed a practical checklist (see Online Resource Table 2). The checklist should assist anyone planning to implement a spine care programs in their local communities. The checklist may also be used when assessing existing resources and to provide information on what additional resources are necessary to provide a specific level of spine care.

For the majority of patients with spine-related concerns as found in Class 0, I, II, low levels of resources need to be provided in the form of facilities and equipment and emphasis should be placed on knowledge and skills of healthcare providers. In these settings, an emphasis on clinical training of evidence-based interventions appears to be the primary resource which is required. High levels of resources are required for only a few patients with spine-related complaints who have severe disorders (Class IVb and Class V).

Community-based and self-care

The GSCI articles on noninvasive care, public health and psychosocial interventions recommend an emphasis on self-care and community-based care [11, 13, 18], which may be achieved through education to avoid misunderstanding of the prognosis and catastrophizing of spine pain. Education and prevention is a component of spine care that is often emphasized in guidelines but is difficult to put into practice. This is especially true if providers in low- and middle-income countries spend only a few minutes with each patient [30]. A study in rural South Africa noted that the community was not involved in healthcare management for most health issues, nor were users involved in their personal health management [31]. It is probable that any movement for community-based and self-care management of spinal disorders would fall on the shoulders of the primary spine care providers unless it is possible to persuade government agencies to consider a program within their public health resource budget [22].

Primary spine care

In the GSCI model of care, primary spine care is delivered by healthcare providers with training and skills in evidence-based spine care [7]. This is consistent with the recommendations of others who have looked at the skills required to manage patients with nonspecific spine pain [32, 33]. Necessary skills include the initial assessment of patients, triage for red flags suggestive of serious pathology, documentation of psychological or social flags and the management of patients with nonspecific pain and related disability (Class I and II) [11, 18]. The latter would include patient and community education and noninvasive, low technology, low-cost interventions for symptom relief. Primary spine care providers would be responsible for referral and coordinating care for complex spinal disorders that may require secondary and tertiary spine care interventions (Class III, IV and V). It is expected that primary spine care clinicians would provide community-based information and encourage self-care when that is the most appropriate care (Class 0, I).

Primary spine care services can be provided by a single clinician or a team of clinicians, who, in combination, possess the knowledge and skills to provide evidence-based spine care [7]. In many settings, the only available clinicians are primary general care providers such as family physicians who have limited understanding of current evidence-based recommendations for patients with spinal disorders. This knowledge gap in spine care is the “ignorance of or unwillingness to follow evidence-based practice recommendations” [34]. Increased training of primary general care clinicians in spine care might be a solution. This requires an educator who understands current guidelines. This education responsibility logically would fall within the domain of the primary spine care clinician. This, however, is not always feasible. Unfortunately, for 50% of the global population, primary general care medical physicians spend 5 minutes or less with their patients [30]. By having a primary spine care clinician present, the general primary care provider could be more available to attend to other health concerns.

Secondary spine care

Secondary care is often provided at the district hospital level and includes emergency care, some diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing, inpatient and surgical facilities. Secondary care is considerably more expensive and resource intensive than primary care [35, 36]. Providers at the secondary spine care level tend to have specialist training but not subspecialty training. Secondary spine care services typically include short-term interventions that require one or more of the following: acute trauma and emergency care, hospitalization, routine surgery, consultation, injections, and rehabilitation. Ideally, the resources to provide psychological and social interventions, as well as some level of pharmaceutical care and spine surgery, would exist in this setting.

Secondary spine care is accessed typically through a referral from a primary spine care provider. In order to be utilized efficiently, only patients requiring care not available at the primary spine care level should be seen in the secondary spine care setting. In addition, when the secondary spine care intervention is completed, the patient should be referred back to the primary spine care setting for ongoing care if indicated. This would avoid stressing the resources at the secondary care level when care can be provided at the primary care level.

Tertiary and quaternary spine care

Tertiary spine care is specialized medical and surgical care for complex, serious and unusual spinal disorders that cannot be managed at the primary or secondary spine care levels. This level of care requires the highest level of resources and is commonly carried out in large inpatient hospitals [37]. Care is provided primarily by clinicians with subspecialty training in such fields as rheumatology, neurology, infectious disease, oncology and most internal medicine subspecialties as recommended in the GSCI care pathway for Class V diseases [6]. The tertiary spine care setting would also require surgeons with advanced spine surgical skills and the supporting surgical infrastructure and personnel to manage the most complex surgical procedures that may be necessary to address severe spine trauma and deformity (Class IVb) and destructive spine pathology (Class V). Typically, tertiary care facilities have advanced diagnostic equipment and intensive care units. Tertiary spine care should also have the resources to manage cases of chronic incapacitating spine pain that have been unresponsive to primary and secondary spine care. This may require resources such as advanced pharmaceuticals, psychological, surgery or multidisciplinary cognitive-behavioral care. In some cases, patients may require treatment for co-morbidities or health conditions that are related to but not generated from the spine.

Beyond tertiary is quaternary care, which is the most resource intense and complex level of surgical and medical care available. Quaternary care is provided at university or research institutions, typically utilizing experimental procedures. Quaternary care is rarely found in low-income countries and therefore may be a low priority. The care provided at the tertiary spine care level requires the highest resource intensity and should be limited to those few cases which cannot be managed at the primary and secondary spine care levels. The inappropriate referral to tertiary care can result in significant and unnecessary excessive cost and use of resources associated with such referrals [38].

Optimization and integration of spine care with existing resources

Developing countries face the challenge of immense needs for health services dwarfing the limited resources available in already overloaded and fragile systems. Twenty criteria have been proposed to assist with decision making around how to best use these limited resources [39]. Similar to the resource needs identified in the GSCI model, a number of these twenty criteria focus on the characteristics of the healthcare provider delivering care. In the GSCI model, knowledge and skills are considered the most important resources to provide care. The collaborative, interprofessional care in high-income countries has a number of benefits that may be useful in clinics with fewer resources. Interprofessional care has been associated with increased quality of care and indicators of safety [40] as well as improved clinical efficiency, improved skills, greater levels of responsiveness, more holistic services and higher levels of innovation and creativity [41, 42]. WHO has identified that interprofessional practice is associated with better outcomes in family health, infectious disease, humanitarian efforts and noncommunicable diseases [43]. In addition, improved outcomes in chronic diseases have been associated with interprofessional care [40].

For example, in Canada, there were long wait times for advanced diagnostic imaging and specialist care, rising costs and no improvement in patient outcomes for low back pain. A primary care spine-focused clinical assessment program was piloted that showed that for those receiving regular care, 100% of computed tomography and 60% of magnetic resonance imaging were unnecessary and did not improve clinical outcomes [44]. However, patients who received primary care level management had improved outcomes and cost savings. If primary spine care could be engaged earlier, wait lists and access to specialty services may be alleviated and this would ensure appropriate allocation of resource utilization. Educating the primary care health workforce to provide primary care spine-focused assessments may help in resource-poor communities to ensure that the available infrastructure and resources have the greatest impact [45].

Another example is the World Spine Care program in Botswana that identified challenges of establishing clinical facilities in a poorly resourced community. In collaboration with the Botswana Ministry of Health, World Spine Care developed a primary spine care clinic in a rural community by adapting a facility provided by the government. This allowed for the delivery of spine care with few physical resources. In this community, the most important factor was a primary care clinician trained in evidence-based spine care. This allowed for the provision of spine care locally without having to refer people with common spine-related complaints to secondary or tertiary facilities. Primary spine care delivery provided community-based education including exercise programs and the referral of patients to the regional district hospital for imaging, laboratory and medical services not available at the community clinic [46]. The success of implementing this primary spine care clinic resulted in a request for implementation of a second clinic in the district hospital outpatient setting. These experiences have demonstrated that the spine care needs of a community can be adapted to resources as they become available and integrated into existing health structures.