Ram Chaddha, MD; Swapnil M. Keny, MS, FCPS, D'Ortho

Curr Orthop Pract. 2017;28(1):23-30.

This article reviews the current concepts in the diagnosis and management of spondylolisthesis and presents the views of experts on this enigmatic and challenging deformity. It examines the concepts of anatomical indices in spondylolisthesis and compares the outcomes of various recent studies for the diagnosis and management of spondylolisthesis.

This article reviews the current concepts in the diagnosis and management of spondylolisthesis and discusses the views of experts on this enigmatic and challenging deformity.

The incidence of degenerative spondylolisthesis seen in women is twice that compared with men.[4,5] The anatomical differences leading to it are believed to be increased pelvic incidence, L4 vertebral inclination, and facets that are oriented more sagittally in women.[6] The incidence of isthmic spondylolisthesis is reported to be about 5% to 6% in the adult population and about 12% in the adolescent population involved in high-impact sports such as football, performance athletics, or gymnastics, and in patients suffering from Scheuerman's disease.[7]

Spondylolysis is considered to be congenital predisposing factor to spondylolisthesis, with an incidence as high as 69%.[8]With a high incidence of sacral spina bifida reported,[9]mechanical stresses on a dysplastic spine are considered important etiologic factors

The angle between the horizontal line and the sacral upper endplate (Figure 1).

The angle between the vertical line and the line joining the midpoint of the sacral upper endplate and the axis of the femoral heads (Figure 2).

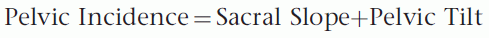

Pelvic Incidence (PI)

The angle between the line joining the center of the upper endplate of S1 to the axis of the femoral heads and a line perpendicular to the upper endplate (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pelvic incidence.

Correlation Between Anatomical Pelvic Parameters

Pelvic tilt is a measure of the spatial orientation of the pelvis, which varies according to position, with a greater or lesser degree of tilt forwards or backwards in relation to a transverse axis passing through the two femoral heads. In the standing position, the mean pelvic tilt angle, which is open at the back, is 13±6 degrees.[10] In a subject who is standing, the pelvis is inclined forward slightly. The greater the angle of pelvic tilt, the further the center of gravity is projected behind the femoral heads.[11,12] As pelvic tilt increases, the sacral plateau becomes more and more horizontal, while consequentially the body of the sacrum becomes vertical.

The degree of the sacral slope (SS) determines the position of the lumbar spine, since the sacral plateau forms the base of the spine. A retroverted pelvis has a high pelvic tilt and a low sacral slope and vice versa. Since the pelvic incidence is the sum total of PT+SS, a vertical sacral endplate is associated with an anteverted pelvis, and a horizontal sacral end plate is associated with a retroverted pelvis. Since the value of the incidence is fixed for a given patient, the sum of the pelvic tilt and the sacral slope is invariable, and as one increases, the other necessarily decreases. In other words, for a given incidence, a specific pelvic tilt will be associated with a specific sacral slope.

Correlation Between Pelvic Incidence and Lumbar Lordosis

The linear correlation between lumbar lordosis and sacral slope has been well established by Stagnara et al.[13] Considering the contribution of the sacral slope to the value of pelvic incidence, the low value of pelvic incidence implies low values of pelvic parameters and a flattened lordosis; a high value implies well-tilted pelvic orientation and pronounced lordosis (Figure 4). A thorough understanding of these spinopelvic parameters are essential when instrumenting the lumbar spine and the sacrum, since restoration of the lordosis and the extent of instrumentation to the correct level are essential to the success of the construct. This means that more the pelvic incidence the more rod contouring is needed to restore the sagittal spinal balance.

Figure 4.

Correlation between lumbar lordosis and pelvic incidence.

Classification

Original Classification System of Lumbosacral Spondylolisthesis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Original classification system of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis.

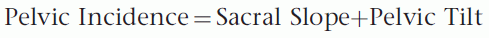

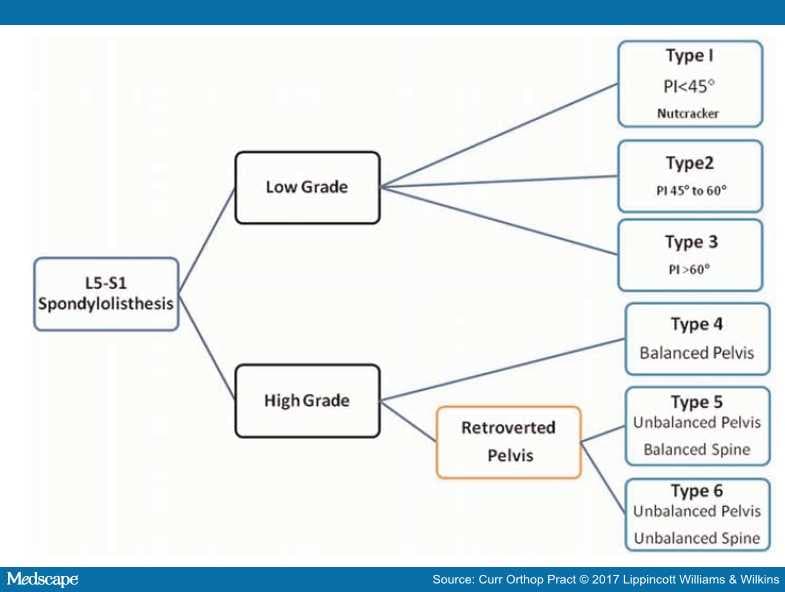

The etiology and degree of slip have been the cornerstones of the previous classifications. However, these classification systems do not provide guidelines to the natural history or the management of spondylolisthesis. The classification proposed by Mac-Thiong and Labelle[14] in 2005 adds clarity to the Marchetti and Bartolozzi[15] classification. Eight distinct subclasses were developed based on the grade of slip, the degree of dysplasia, and the balance of the pelvis in the sagittal plane.

Spinal Deformity Study Group (SDSS) Classification

The Spinal Deformity Study Group validated this classification and with the help of additional observers proposed a refinement and a simplification to this classification by removing the degree of dysplasia and basing the classification on the grade of slip, the sacropelvic balance, and the spinopelvic balance.

Spinopelvic Balance. Spinopelvic balance is defined by the plumb line drawn vertically downward from C7. If this line falls over or behind the femoral heads, then the spine is considered as balanced. If it falls in front of the femoral head, then spine is considered unbalanced.

Sacropelvic Balance. Sacropelvic balance is defined as a high sacral slope and a low pelvic tilt (anteverted pelvis). An unbalanced sacropelvis has a low sacral slope and a high pelvic tilt (retroverted pelvis). The group found that spinopelvic balance was always maintained in low-grade spondylolisthesis and high-grade spondylolisthesis with a balanced sacropelvis. Whereas spinopelvic balance was lost in high-grade deformities with a unbalanced sacropelvis. In other words an unbalanced sacropelvis was considered the most severe deformity because it caused a sagittal plane spinal imbalance (Figure 6)

Figure 6. The SDSS classification of lumbosacral spondylolisthesis.

Mechanics of Spondylolisthesis

The isthmic spondylolisthesis occurs as a result of structural discontinuity between the middle and the posterior columns of the spine at the level of the pars interarticularis. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, the factors seem to be sagittal orientation of the L4–5 facets in certain individuals,[16,17] W-shaped facets,[18] facet joint osteoarthritis,[19] synovial cysts of the facet joints,[20] increased fluid signal in the facet joint,[21]and facet fusion.[22]

Evaluation of Instability

More than 8% of sagittal translation of one vertebra over the other on lateral flexion extension radiographs has been suggested as significant instability according to many studies.[23–26] In this situation, spinal fusion is considered to be treatment of choice in patients who are refractory to other treatments.[27] Flexion and extension radiographs in lateral decubitus position are considered the gold standard.[26] Liu et al.[28] has found that a combination of a standing lateral radiograph of the lumbar spine and a supine sagittal MRI has a better ability to detect mobility compare to flexion-extension views alone.[28] Segebarth and Kurd[29] retrospectively analyzed 109 patients with instability on flexion-extension radiographs. Twenty-eight percent of their patients had degenerative spondylolisthesis that was not diagnosed on supine MRI.

Surgery in Spondylolisthesis

The SDSS classification defines clear guidelines for surgery in isthmic spondylolisthesis. The Spine Patient Research Outcome Trial (SPORT) demonstrated better outcomes for patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis treated surgically than those treated nonsurgically over a period of 4 yr.[30,31] Pearson et al.[32] recently published the treatment effect (TE) predictors in SPORT based upon the comparison of improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index in patients who had undergone surgery compared to those who were treated nonsurgically. They identified 12 TE predictors that positively affected the outcome of patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Age 67 yr or younger, female sex, no stomach problems, having neurogenic claudication, reflex asymmetry, opioid use, not taking antidepressants, dissatisfaction with symptoms, and anticipating a high likelihood of being pain free with surgery remained significant independent predictors of greater TE.

Defining Surgical Criteria

Sadiq and Meir[33] defined criteria for surgery in spondylolisthesis by doing an extensive overview of literature (Table 1)

Table 1. Criteria for surgery in spondylolisthesis| Group | Definition | Indications for surgery |

|---|

| I-A | Children and adolescents with low-grade spondylolisthesis | Failure to respond to prolonged conservative management. Indications include progressive slip, intractable back and leg pain and neurological deterioration |

| I-B | Children and adolescents with high-grade slips | Slips greater than 50%. Neurological symptoms, progression and mechanical deterioration of deformity |

| II-A | Adults with low-grade spondylolisthesis | Failure of nonoperative treatment |

| II-B | Adults with high-grade spondylolisthesis | Symptomatic patients with low back pain and/or radicular pain in high-grade slips |

| III-A and B | Adults older than 40 y with low-grade spondylolysis and degenerative spondylolisthesis | Persistent or recurrent back or leg pain or neurogenic claudication and failure of conservative trial of treatment, along with progressive neurology or bladder or bowel symptoms |

Debates in Spondylolisthesis

Decompression Without Fusion Compared With Noninstrumented Decompression With Posterior Fusion in Degenerative Spondylolisthesis

Joaquim et al.[34] reported a metaanalysis of the literature and identified patients in whom decompression without instrumentation led to medium to long-term good results. They associated a facet angle of more than 50 degrees, a disk space of more than 6.5 mm, the presence of low back pain rather than lower extremity symptoms, the presence of hypermobility in the listhetic level on dynamic radiographs (>1.25 to 2 mm), and resection of the posterior elements was associated with a less favorable outcome.

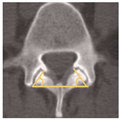

The Facet Angle (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Facet angle (Blumenthal et al.35).

This is measured by calculating the angle generated by connecting the two endpoints of each facet on a preoperative axial lumbar CT (midcut through the disk) and a line connecting the two dorsal points of each facet joint. When the facet angles are different, the average value is used. Facet angles of more than 50 degrees were associated with 39% rate of reoperation in one study.[35]

Posterolateral Fusion Versus Interbody Fusion

Gottschalk et al.[36] did a comparative analysis of patients undergoing posterolateral fusion alone or posterolateral fusion with an interbody fusion in 179 patients. They found no statistical differences in Oswestry Disability Index, fusion rates, or cost/value at more than 3 yr. They concluded that both procedures had equivalent results in degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Liu et al.[37] reported a metaanalysis of eight studies published in the literature to compare the outcomes of a circumferential fusion with that of posterolateral fusion for isthmic listhesis and found no differences in clinical satisfaction, complication rates, fusion rates, reoperation rates, operating time, or blood loss but stated that stabilization of three columns helps to enhance the fusion rate, maintain intervertebral height, and restore sagittal alignment.

Interbody Graft Versus Interbody Cage

Sivaraman et al.[38] carried out a prospective study comparing the two modalities of fusion in degenerative spondylolisthesis in 59 patients and found that a cage does not confer any significant advantages in terms of restoration of lumbar lordosis, improvement in clinical symptoms, or relief of pain postoperatively.

Reduction versus in Situ Fusion for High-grade Slips

Gandhoke et al.[39] reported a multicenter, retrospective analysis of 25 patients who had attempted reduction for high-grade slip (grade 3 and over) and found that reduction in conjunction with wide neural element decompression and instrumented arthrodesis is safe, effective, and durable with low rates of neurologic injury, favorable clinical results, and high fusion rates.

Ruf et al.[40] suggested the four key techniques for reduction of high grade spondylolisthesis:

- wide lateral exposure of the nerve roots

- removal of potentially compressive disk material or bony sacral ledge

- avoidance of excessive distraction, and use of small interbody cages

- adequate correction of the sacral retroversion to relieve tension on the nerve roots

Minimally Open Surgery (MIS) Versus Open Surgery (OS) for Spondylolisthesis

Lu et al.[41] did a meta-analysis of 10 studies of 602 patients for MIS versus OS for the management of spondylolisthesis with up to grade 2 slips. Both groups reported fusion rates ranging from 91.7% to 100%. They concluded that spinal fusion by MIS is a safe and effective approach in low-grade spondylolisthesis.

Navigation-assisted Screw Placement

Boon Tow et al.[42] performed a prospective comparative study in patients with single-level degenerative listhesis who underwent O-arm navigation-assisted screw placement and free-hand screw placement and found no significant difference in the accuracy of screw placement between the groups.

Changing Concepts and Controversies in the Fusion Modalities

Interlaminar Instrumented Fusion

Cuéllar et al.[43] prospectively analyzed a group of 33 patients, two of whom had grade 1 degenerative spondylolisthesis who underwent interlaminar interbody fusion after decompression by placement of allograft-supported spinous process plates and reported excellent results. These results, however, cannot be extrapolated to higher grades of slips in degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Rh BMP2 in Fusion for Spondylolisthesis

Schroeder et al.[44] reported a dramatic decrease in the use of Rh BMP-2 for fusion in degenerative spondylolisthesis with the two most important reasons being cost and the high rate of complications. An independent review of two published industry-supported studies concluded that there was no clear advantage to using Rh BMP-2 for fusion, and the use may lead to complications.

Bioactive Glass as Bone Substitute

Frantzén et al.[45] published their 11 yr results after treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis using a combination of autologous bone graft and bioactive glass on either side. The results showed a fusion rate of 88% at L4–5 and L5-S1 with bioglass and 100% at both levels with autologous bone graft. They concluded that bioactive glass as a bone graft extender can be considered as a good alternative in spinal surgery in the future.

Transsacral Fusion in High-grade Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

Sasso et al.[46] reported their results of transsacral strut grafting for high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis without reduction in 25 patients with a mean follow-up of 39 mo. They concluded that despite no reduction in translational deformity, the transsacral strut graft technique offers excellent fusion results, good clinical outcomes, and prevents further sagittal translation and progression of lumbosacral kyphosis.

Shedid et al.[47] reported the results of a novel, minimally invasive technique for treating high-grade lumbosacral spondylolisthesis using a a percutaneous transsacral rod in three patients. They believe that a posterior transsacral axial rod creates a structurally sound anterior column, eliminating the problems of bone grafts and those associated with the anterior approach to treat these deformities. They published favorable results using this technique.

Conclusion

The principles of management of symptomatic spondylolisthesis have remained consistent over the years. Understanding of the biomechanics of spondylolisthesis, implants, and reduction techniques and the fusion modalities has, however, evolved.