Godefroy Hardy St-Pierre, MD, MPH; Michael H. Yang, MD; Jonathan Bourget-Murray, MD; Ken C. Thomas, MD, MHSc; Robin John Hurlbert, MD, PhD; Nikolas Matthes, MD, MPH, PhD. Spine. 2018;43(4):275-280.

Study Design. Systematic review.

Objective. To elucidate how performance indicators are currently used in spine surgery.

Summary of Background Data. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act has given significant traction to the idea that healthcare must provide value to the patient through the introduction of hospital value-based purchasing. The key to implementing this new paradigm is to measure this value notably through performance indicators.

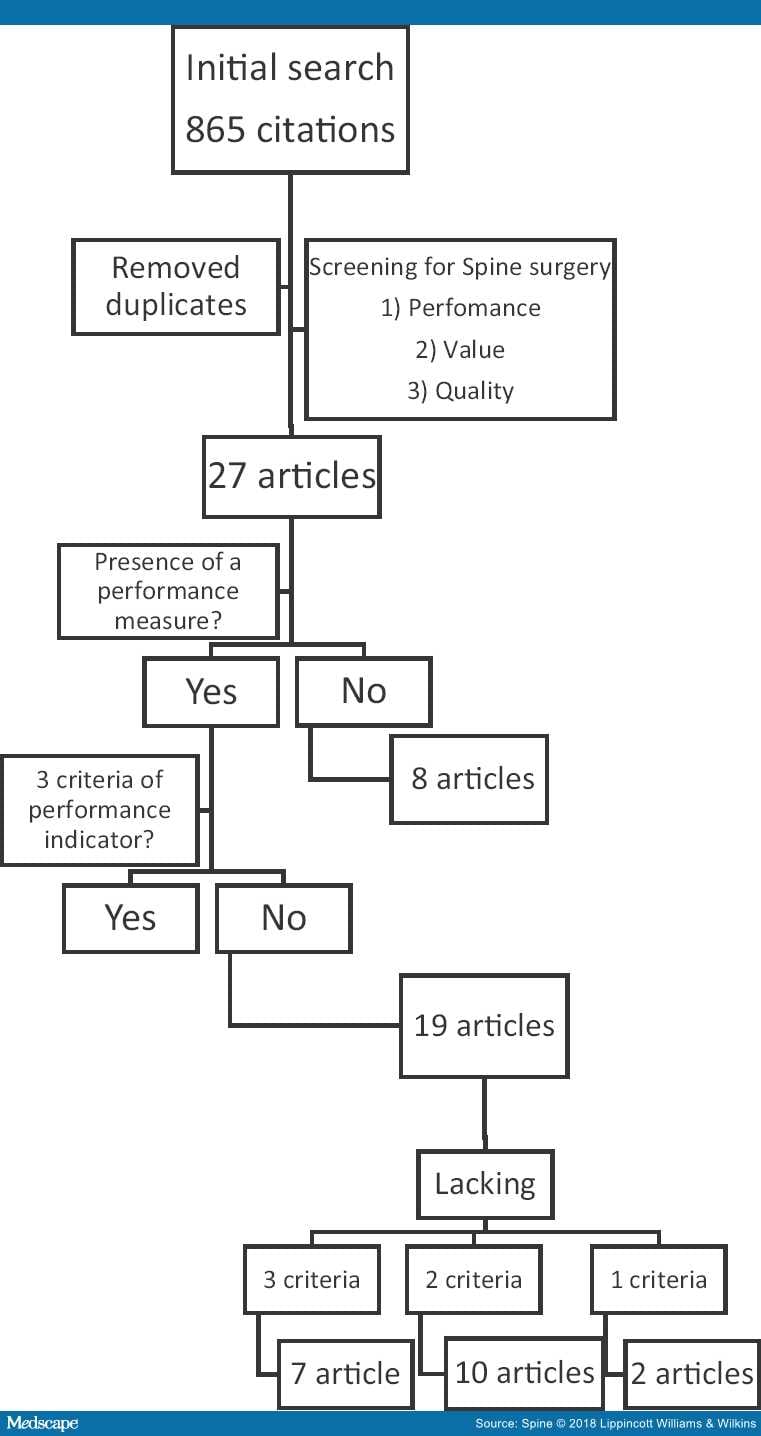

Methods. MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, EMBASE, and Google Scholar were searched for studies reporting the use of performance indicators specific to spine surgery. We followed the Prisma-P methodology for a systematic review for entries from January 1980 to July 2016. All full text articles were then reviewed to identify any measure of performance published within the article. This measure was then examined as per the three criteria of established standard, exclusion/risk adjustment, and benchmarking to determine if it constituted a performance indicator.

Results. The initial search yielded 85 results among which two relevant studies were identified. The extended search gave a total of 865 citations across databases among which 15 new articles were identified. The grey literature search provided five additional reports which in turn led to six additional articles. A total of 27 full text articles and reports were retrieved and reviewed. We were unable to identify performance indicators. The articles presenting a measure of performance were organized based on how many criteria they lacked. We further examined the next steps to be taken to craft the first performance indicator in spine surgery.

Conclusion. The science of performance measurement applied to spine surgery is still in its infancy. Current outcome metrics used in clinical settings require refinement to become performance indicators. Current registry work is providing the necessary foundation, but requires benchmarking to truly measure performance.

Level of Evidence: 1

Since the dawn of modern surgical care, surgeons of all specialties have been keenly interested in providing a better quality of life for their patients. Outcome pioneers such as E. Amory Codman introduced the idea of "end result" over a century ago in 1905.[1] Morbidity and mortality conferences have helped to develop a strong sense of personal responsibility in generations of surgeons, but Dr. Codman himself had grander plans for his idea: what if end results were collated in all hospitals[2] and reported at a national level? Realization of such an endeavor took several decades, but it can now be said with the advent of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program[3] (NSQIP) that Dr. Codman's vision may finally be coming to fruition.

Since 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act[4] has given significant traction to the idea that hospitals and physicians must provide "value" to the patient by reducing costs and improving outcomes.[5] First introduced by Porter,[6] value is often simplified as quality over cost.[7–9] The intent behind any value driven process is to minimize the cost by maximizing the quality, often considering a threshold of minimal quality and a threshold of maximum cost. In the context of the current US healthcare system, value is meant to be observed from multiple angles at once. Quality is likewise multidimensional, but the weighting of its myriad facets to decide what should take precedence is often complex. Surgeons are best positioned[10]to propose definitions that will create new benchmarks for quality of care to reconcile the possible conflict between quality and cost.[11]

One of the key tools available to the healthcare industry is the performance indicator. A succinct definition provided by the Health Information and Quality Authority of Ireland[12] reads as follows: "Performance Indicators are measures of performance that are used by organizations to measure how well they are performing against targets or expectations. Performance indicators measure performance by showing trends to demonstrate that improvements are being made over time. They also measure performance by comparing results against standards or other similar organizations."

Performance indicators most pertinent to the clinical aspect of spine surgery would be termed "outcome" indicator as per the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.[13] Although multiple definitions exist as to what criteria define an outcome performance indicator[14–16] in healthcare, we aimed to simplify its nature by summarizing the definition of the National Quality Forum (NQF) in three criteria: established standard, risk adjustment, and benchmarking. A performance indicator first and foremost rests on a scientific consensus via its use of an established standard in its measure. For example, quantifying pain on a scale of 1 to 72 might provide interesting nuances, but the use of 1 to 10 Visual Analog Scale (VAS) would be considered standard. Second, the performance indicator is narrowly defined for a specific population in a specific context, and its measure needs to be adjusted when applied to a subpopulation with a higher risk: this speaks to the notions of applicability and attribution of causality.[13] For example, it could be inferred on a performance indicator measuring fusion rate, that smokers would not need to attain a similar level to be considered a success, given their intrinsically lower fusion rate. Finally, this leads to the concept of benchmarking. The idea of measuring performance implies that a certain level was reached or failed to be reached. It is the comparison of an actual result with the expectation, the benchmark. A performance indicator without this last element can be an interesting prototype, or pilot measure, but it does not constitute a performance indicator until it has measured something.

The purpose of this review was to examine the literature for evidence of performance indicators that satisfy the above criteria specific to spine surgery and to elucidate how such performance indicators are currently used in spine surgery. Finally, we undertook to look for methodologies proven successful in establishing similar benchmarks in other specialties.

An electronic literature search was performed adhering to the criteria of PRISMA-P (appendix, http://links.lww.com/BRS/B287). MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, EMBASE, and Google Scholar were searched for studies reporting the use of performance indicators specific to spine surgery. Entries were included from January 1980 up to July 2016. Our extended search added the terms quality indicators and value indicators and substituting indicators for the terms markers, index, standards and measures. Only articles in English were included. All identified abstracts were screened and full text articles were retrieved when abstracts were deemed relevant. The search was further broadened by investigating the grey literature.

Studies included were abstracts pertaining to (1) performance specific to the context of spine surgery; this was extended to the concepts of (2) value, and (3) quality again specific to spine surgery. All full text articles were then reviewed to identify any measure of performance published within the article. This measure was then examined as per the three criteria of established standard, exclusion/risk adjustment, and benchmarking to determine if it constituted a performance indicator (Figure 1). The grey literature was searched through reports from the WHO, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), National Health Service (NHS), and Health Canada. Two repositories of performance indicators were specifically searched manually for spine specific indicators namely the NQF and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Data extraction was planned to be performed by three authors (GHStP, MY, and JBM) independently by completing a predetermined extraction form in the event a performance indicator was identified. Any disagreement was to be discussed and ultimately resolved by the senior author (RJH).

Figure 1.

No funding agency or sponsor was involved in this review. Studies were initially selected by the first author then abstracts reviewed by three authors independently. All authors had access to the entire dataset of studies prior to elimination. Risk of bias and meta-bias was not assessed given the exploratory and qualitative nature of the systematic review. The strength of the body of evidence was to be evaluated in a qualitative manner should performance indicators be identified.

The initial search yielded 85 results among which two relevant studies were identified.[17,18] The extended search gave a total of 865 citations across databases among which 15 new articles were identified.[19–34] The grey literature search provided five additional reports,[35–39] which in turn led to six additional articles.[40–45] A total of 27 full text articles and reports were retrieved and reviewed.

Eight articles did not contain any performance measure.[17,19,20,25–29]Chiefly concerned with both the notion of performance and value, those articles proceed to define or explain those respective ideas in the context of spine surgery. Of note, Rihn et al[25] warn that although established standards need to be at the core of performance indicators, scientifically relevant information such as the minimally important clinical difference (MCID) might not be clinically relevant, and as such, should probably not be considered a sufficient threshold when creating a clinical benchmark. This underscores the importance of clinician involvement at the very genesis of those measures[19] to ensure they have clinical usefulness. In another important article, Rihn et al[26] present an important caveat to the "low hanging fruit" of administrative data. Taken alone and with limited context, process measures should not be termed performance indicators as they do not adequately represent the clinical reality underpinning quality of care.[26]Spine surgeons should be vigilant and proactive in suggesting themselves what constitute value in their field lest it is defined for them.[20] Overall, these articles cement that performance lies at the heart of value,[17,19,25,28,29] and the key component to its measurement is the performance indicator.

Among the remaining 19 articles presenting a measure of performance, none had the three predefined criteria of a performance indicator. We organized those articles on the basis of how many criteria they lacked, either only one,[23,35–37] two,[18,21,22,24,32,34,38,39] or all three.[30,31,33,40–43]

The seven articles lacking all three criteria all had a singular purpose: establish a standard of performance. The series of articles linked to the very large Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) database[40–43] were indeed used as a comparative standard by the Cleveland Clinic group in its own reports,[36,37] to give perspective to its own results. The purpose of the SRS articles, however, did not go beyond this prior step which anchors the performance indicator. Similarly, two articles tried to define standards in the realm of patient satisfaction.[30,31] Finally, the measure SQ56 for metastatic spine compression[33] from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is a good institutional example of a quality standard. Once implemented and with proof of its widespread acceptance and applicability, compliance with SQ56 would become an established standard.

Of the 10 articles lacking two criteria, the presence of an established standard was the common characteristic of all reports.[18,21,22,24,32,34,36–39]three of those articles[21,22,24] pertained to the construction of large registries for which the importance of using consensual and broadly accepted measures for outcomes were outlined. Two articles[18,38]discussed the Spine SCOAP registry without directly acknowledging its unique step forward in incorporating risk-adjustment in its structure.[23] The grey literature search revealed the public disclosure of spine surgery mortality per surgeon by the NHS,[34] although no risk-adjustment or benchmarking were used. The reports of the Cleveland Clinic on their spine surgery outcomes were similarly lacking: despite availability of 2011 and 2013 results,[36,37] those were not compared side to side in the 2013 report to allow a certain benchmarking. Comparison with outside standards was suggested instead[38–43] using analysis of large databases as a surrogate for a US norm against which the Cleveland Clinic could be positioned.

Lastly, two articles lacked only one criteria,[23,35] and again, this was surprisingly the same one: benchmarking. It became apparent that there was seemingly a logical progression towards the crafting of a performance indicator which paralleled our criteria. In their description of the Spine SCOAP registry and its results, Lee et al[18] insist on the importance of risk-adjustment without which proper comparison between potentially disparate populations cannot take place. The NQF endorses one measure of spine surgery performance:[35] NQF #2643 average change in functional status after lumbar spine fusion surgery. Based on the ODI and appropriately risk-adjusted, it lacks accompanying expected versus actual results. However, the publication by a center of its application of NQF #2643 would constitute the first published performance indicator in spine surgery.

Our review of the literature revealed that the spine surgery community is attempting to embrace the concept of performance measurement. However, there is still significant confusion as to what exactly constitutes a performance indicator.[28,44]

Considering our initial definition, our review of the literature allows several important observations. First, outcomes in themselves are not performance indicators but rather an essential component in their makeup. A true performance indicator allows for the definition of expected thresholds and targets, establishes trend over time, and allows comparison with established standards. Outcome data without an established standard is more appropriately termed a metric.[45] Unfortunately, widely accepted standards are yet to be established for spine surgery outcomes, but the growth of large registries is attempting to fill that void.[24] Second, the concepts of exclusion criteria and risk adjustment are critical to crafting a performance indicator.[46] Although a detailed consideration of these concepts is beyond the scope of this review, many of the retrieved articles[17,21–30,32–33] clearly defined inclusion/exclusion criteria and/or provided risk adjustment associated with their reported outcomes. It is essential that performance indicators are applied uniformly to comparable groups of patients in comparing one population against another. Finally, articles simply reported current performance without target or expectation; reluctance to set a predetermined goal in a competitive and litigious environment is understandable given the potential consequences of substandard performance. However, absconding this responsibility opens the door to purely administrative benchmarks, for example, CMS defining an acceptable rate of postoperative surgical site infection as 0% ("never event").[47] No credible surgical series or large registries have reported a 0% postoperative infection rate; it is neither practical nor achievable.[39,40]

Despite disappointing evidence for established performance indicators, our review revealed a relative consensus among the spine surgery community concerning outcome metrics that might be used in the crafting of such indicators. The Visual Analog Scale, Oswestry Disability Index, Neck Disability Index, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, and Short Form-36/Short Form-12 are almost ubiquitous throughout the literature. This consensus is evidenced by enthusiasm in the construction of and participation in large data registries currently in use. The capacity to set standards or benchmarks from these initiatives is obvious.

Spine surgeons realize the potential peril of exclusively using administrative data[25–28] to determine the success of their surgeries; performance indicators representative of the patient's outcome are paramount. Especially worrisome is the concept of public disclosure of mortality or complication rates associated with an individual surgeon's name.[48] The fear of misinterpretation of this data or inappropriate risk adjustment is probably justified, but prior experiences notably in the United Kingdom concerning cardiac surgery after the Bristol Enquiry[49] suggests that surgical attitudes toward this drastic change evolve rapidly.[50] Public reporting becomes yet another fact of surgical practice and an established audit system does lead to improved outcomes. On the other hand, internal audit and feedback systems such as the one instituted in the Department of Head and Neck surgery of the MD Anderson Cancer center[51,52] have also shown the ability to drive improved outcomes without the pressure of public disclosure.

The NSQIP provides an interesting blueprint for what could potentially come next in our field, especially as it has already extended its data collection and its risk calculator algorithm to spine procedures. The ultimate goal would be for an individual spine surgeon to know precisely their own performance, benchmarked against itself, local colleagues and national average, stratified by procedure and risk adjusted to its specific practice pattern. Initially created in the Veteran Affairs system in the United States,[53] NSQIP was endorsed and subsequently taken over by the American College of Surgeons. The process was to first establish robust and agreed upon measurements of surgical outcomes with standards every surgeon would use: mortality, re-operation, postoperative infection, specialty appropriate scales, and so on. Although aggregating those measures in a large database, specific preoperative patients' characteristics were collected as well to segregate patients in appropriate risk categories: this then allowed reporting of risk-adjusted outcomes. The final step was benchmarking, or comparison with pre-established targets. Using its own data from formative years, NSQIP determined what constituted an acceptable target and was then able to provide participating hospitals with feedback. Furthermore, the extent of the data collection allowed national benchmarking or comparison among hospitals across the United States. This is potentially already taking place for spine surgery, but this data have not been published.

All reports concerning spine surgery data from the NSQIP focus on harnessing the massive database for the traditional purpose of identifying risk factors associated with various poor outcomes.[54–57] In comparison, three general surgery performance indicators[58] have been made public on hospitalcompare.com, the CMS sponsored website.

Coming back to a spine centric perspective, databases such as National Neurosurgery Quality and Outcomes Database (N2QOD) and Surgical Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program (SCOAP) have the potential to establish performance indicators and seem to be headed in that direction. The critical step apparently remains the benchmarking process, as evidently no center would want its performance to fall below the predetermined level. NSQIP could have already achieved that step, but its data remain private for now.

The science of performance measurement applied to spine surgery is still in its infancy. Current outcome metrics used in clinical settings require refinement to become performance indicators. Registry work is providing the necessary foundation. Future initiatives need to develop performance indicators which have clear inclusion/exclusion criteria, clear benchmark of comparison, and minimum expected outcome/improvement. There is a strong will among the spine surgery community to embrace performance indicators and make them relevant markers of patient outcomes.

C/ San Pedro de Mezonzo nº 39-41

15701 – Santiago de Compostela

Teléfono: +34 986 417 374

Email: secretaria@sogacot.org

Coordinador del Portal y Responsable de Contenidos: Dr. Alejandro González- Carreró Sixto