In total, we identified 11 retrospective studies that examined the possible relation between radiographic imaging and treatment strategy. Several studies also described the influence of the omission of radiographs on functional outcome or detection of complications. Unfortunately, these studies were clinically so diverse that it was not possible to pool the data. Based upon the descriptive analysis, it appears that all studies come to essentially the same conclusion. They all suggest that omitting some, or even all, follow-up radiographs of extremity fractures does not have important clinical consequences, such as changes in treatment strategy, a deterioration of clinical outcomes, or missed complications. From the studies we included in this systematic review, no distinction could be made between different fracture locations or fracture types. However, all conclusions were based upon retrospective studies, introducing a high risk of bias and confounding. The level of evidence was low, indicating that these results should be interpreted with caution. We did not identify any prospective studies. As a result, studies included in this review should be regarded as the best available evidence at present.

For other indications, such as low back pain [29], knee osteoarthritis [30], or following paediatric spinal surgery [31] the added value of routine radiographs are being questioned as well. Apparently, for other indications than extremity fractures, radiographs are also obtained routinely and without great impact on treatment strategies. In addition, for direct post-operative check radiographs of, for instance, hip fractures, multiple retrospective studies exist that debate their usefulness or discourage their use [32, 33, 34, 35]. A randomized study investigating the usefulness of direct post-operative control radiographs for operatively treated wrist and ankle fractures is currently being conducted by Oehme et al. [36]. Routine radiographs might resemble low-value care, and omitting them might lead to increased efficiency for the health care system. The American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons released a consensus statement discouraging the use of routine radiographs to monitor fracture, osteotomy, and arthrodesis healing without a clinical indication in the foot and ankle [37]. However, to date, prospective evidence to support this claim is lacking.

In all studies included in this review, the number of changes in treatment strategy based on radiography was low. As depicted in Table 3, it ranged from 0 to 2.6%. The number of complications detected on a routine radiograph, in the absence of clinical symptoms, was similarly low. Both patients and physicians tend to ascertain value to radiographic confirmation of a favourable recovery. However, this review suggests that findings on a routine radiograph that require a change in treatment strategy, in the absence of clinical symptoms, are rare. The presence of clinical symptoms could be a good predictor of an unfavorable outcome, and might justify the use of radiography to rule out a complication. In the randomized controlled trial we are currently conducting [38], reasons to obtain radiographs include: a pain score higher than 6 on a 1–10 Visual Analog Scale, a loss in range of motion, neurovascular symptoms, or a successive trauma to the injured limb. It is clear from our overview that interest in this topic is growing. All but two studies were published in the last 6 years, and quality and precision of the studies improved over time. For example, the older two studies contributed just 2% to the total number of participants and scored poorly on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (three and four points out of nine, respectively). The more recent studies included more participants and, on average, scored higher on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale.

Limitations and strengths

All studies included in this review had a retrospective design and several other limitations in their study design on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. All studies but two had a non-comparative design, and no statistical testing of outcomes was performed. The risk of bias was high, confounding was likely, and the external validity was limited. This resulted in a ‘very low’ level of evidence according to GRADE.

Conclusions in systematic reviews are dependent on the quality and design of studies included. The fact that only retrospective studies were identified and the level of evidence was very low hinders us in making strong recommendations. A second potential limitation was the tool used for assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale is best suited for comparative and prospective non-randomized studies; therefore, this tool might not deliver the best assessment of risk of bias in the current setup. Finally, we limited our search to English and Dutch; therefore, language bias may affect our conclusions. However, no studies in Dutch were identified by the search strategy, and manual screening of the reference lists of included studies did not yield any references in a language other than English. Consequentially, the chance that language bias played a substantial role in the selection process of the systematic review was deemed low.

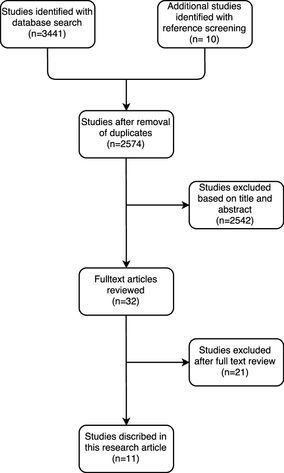

A strength of this study is presented by the fact that the percentage of included studies was very low (0.4%). This indicates that our initial search was broad, and as a result, the risk that important publications were missed was low.