In the last two decades, there has been a significant increase in the burden and costs of spinal disorders throughout the world. This impact has been seen not only in high-income countries but also in low- and middle-income countries [1, 2]. Non-communicable diseases such as spinal disorders are contributing a higher proportion of the total burden of disease than previously considered. At the same time in low- and middle-income countries, minimal health care resources are being expended internally and through international health care priorities to reduce the disability associated with spinal disorders. In high-income countries, such as the USA, there has been a marked and progressive increase in the cost of health care for people with spinal disorders with a concomitant increase in spine-related disability [3, 4].

Disability and costs attributed to spinal pain are projected to increase, which is a concern particularly for low- and middle-income countries where the infrastructure may be fragile and not equipped to cope with a growing burden [5]. There is an increasing call to action by leaders in the spine care community who stress it is essential to prevent the use of practices that are ineffective, harmful or wasteful of limited resources [6]. The concern is that fragmented and outdated models of care fail to address widespread misconceptions in the population and among health professionals about the causes, prognosis, and effectiveness of different treatments for spinal pain [6].

Controlled clinical trials have been the primary tool to assess the benefits and harms of common interventions for the management of spinal pain with the assumption that this will improve outcomes and reduce the costs and disability associated with spinal disorders. These trials have been performed in high-income countries, so little is known about low- and middle-income countries. At the same time, task forces, government, and professional committees have reviewed and synthesized the results of this research to develop clinical practice guidelines. These guidelines have focused primarily on non-specific or axial low back and neck pain although guidelines have also been developed to address specific pathological spinal disorders, such as spinal stenosis, spondyloarthropathies, scoliosis, and radiculopathy. Implementation of these guidelines, however, has proved difficult [7, 8, 9]. The difficulty in implementation and failure of clinicians to follow guidelines in high-income countries has been attributed to complex issues including provider and patient behavior, health literacy, legal, and systems/reimbursement issues.

There are challenges to implementing evidence-based guidelines in any health care community. In many communities, health care providers are scarce [10] or the primary care clinician or team of providers may not have the experience, relevant professional training, or resources to implement evidence-based management for the wide spectrum of spinal disorders. For low- and middle-income countries, resources are scarce [11, 12], thus providers may be less likely to have the skills and resources to manage spine-related concerns. Patients in these settings present with a full spectrum of spine-related disorders such as low back, middle back and neck pain, which might be acute, chronic, and/or episodic or recurrent and associated with varying degrees of impairment of function or activities of daily living. The incidence of chronic diseases in low- and middle-income countries is higher than in high-income countries [13, 14]. As well, primary health care could perform better within the care delivery system in underserved areas [12, 15]. There may be no imaging or laboratory testing facilities readily available at the primary care level and advanced imaging and testing may not be available even at secondary care centers or district hospitals [16]. Some communities have no or few clinicians that commonly manage spinal disorders, such as chiropractors, psychologists or physical therapists. There may be limited access to medical specialists in the fields of psychiatry, rheumatology, neurology, psychiatry, or spine surgery at secondary care and even at the tertiary centers where patients with the most serious spinal pathology are likely to be referred. There may not be resources available to manage the complications of the interventions recommended in guidelines such as gastric bleeding from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), constipation, and addiction from opioids, follow-up care and rehabilitation following surgery and psychiatric and psychological care that often is associated with chronic pain. Thus, there is a need to develop a care pathway that could address these concerns and that could be adapted to the community and available resources.

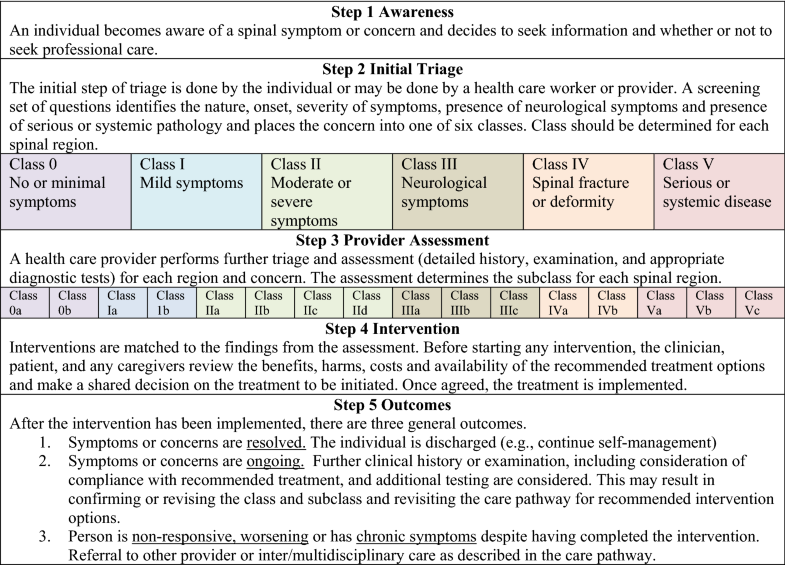

Care pathways are “a complex intervention for mutual (between patient and clinician) decision-making and organization of care processes for a well-defined group of patients during a well-defined period” [17]. Care pathways have been proposed as a means of implementing guidelines into specific clinical settings. A care pathway provides a mechanism whereby multiple guidelines can be integrated and modified to adapt to the available professional and physical resources. They are a means of coordinating health care and to provide a mechanism for integrating evidence-based health care with real-world clinical practice. Chawla et al. [18] describe this process as having the “goal of using high-quality evidence for pathway development and affording physician flexibility in implementation”. Care pathways “are used to reduce variation (in care), improve the quality of care, and maximize the outcomes for specific groups of patients” [19]. Cavlan et al. [20] describe care pathways as being organized by the stages of care and including the full range of interventions that may be offered at each stage. They note that pathways should include all treatments, ranging from primary prevention to rehabilitative services, that may be offered to patients and that care pathways should describe steps that are considered at each stage of care. Whereas most current spine-related guidelines tend to address specific subgroups of patients such as non-specific back or neck pain or pathologies such as stenosis or radiculopathy, a comprehensive care pathway has the capacity to integrate guidelines for multiple spinal disorders into a single clinical decision tree and is, therefore, more applicable in clinical settings with limited professional resources.

There is an increased interest in developing and evaluating care pathways for musculoskeletal conditions including low back pain [21, 22]. However, we are not aware of a care pathway to guide the management of the full spectrum of potential presentations of spinal symptoms, concerns or pathology. This variety includes the most benign questions requiring a public health message through the most severe systemic and life-threatening destructive spinal pathologies while focusing on the most common variations of spinal pain irrespective of location (i.e., neck, middle back, low back, arm, or leg symptoms). However, other care pathways may focus on a particular symptom, such as back pain, or a specific disorder or disease, resulting in a more narrow approach to a patient care pathway. The purpose of this study was to develop a care pathway supported by current evidence-based guidelines that could apply to any person presenting with a spine-related concern, especially those who live in low- and middle-income communities or in underserved communities in high-income countries. At the same time, it was felt to be essential to prevent the use of practices that are ineffective, harmful or wasteful of limited resources and to satisfy reported concerns that fragmented and outdated models of care fail to address widespread misconceptions in the population and among health professionals about the causes, prognosis, and effectiveness of different treatments for spinal pain [6].