Benjamin E Smith; Paul Hendrick; Toby O Smith; Marcus Bateman; Fiona Moffatt; Michael S Rathleff; James Selfe; Pip Logan

Background Chronic musculoskeletal disorders are a prevalent and costly global health issue. A new form of exercise therapy focused on loading and resistance programmes that temporarily aggravates a patient's pain has been proposed. The object of this review was to compare the effect of exercises where pain is allowed/encouraged compared with non-painful exercises on pain, function or disability in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain within randomised controlled trials.

Methods Two authors independently selected studies and appraised risk of bias. Methodological quality was evaluated using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment system was used to evaluate the quality of evidence.

Results The literature search identified 9081 potentially eligible studies. Nine papers (from seven trials) with 385 participants met the inclusion criteria. There was short-term significant difference in pain, with moderate quality evidence for a small effect size of −0.27 (−0.54 to −0.05) in favour of painful exercises. For pain in the medium and long term, and function and disability in the short, medium and long term, there was no significant difference.

Conclusion Protocols using painful exercises offer a small but significant benefit over pain-free exercises in the short term, with moderate quality of evidence. In the medium and long term there is no clear superiority of one treatment over another. Pain during therapeutic exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain need not be a barrier to successful outcomes. Further research is warranted to fully evaluate the effectiveness of loading and resistance programmes into pain for chronic musculoskeletal disorders.

Musculoskeletal disorders are one of the most prevalent and costly disorders globally.[1,2] Low back pain is considered the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide, ahead of conditions such as depression, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, with a global point prevalence of 9.4%.[3,4] Neck pain and other musculoskeletal pain ranks fourth and sixth in terms of years lived with disability, with a global point prevalence of 5% and 8%, respectively.[5,6] In the UK, an estimated one in four people suffer from chronic musculoskeletal disorders,[7] with an estimated economic consequence of 8.8 million working days lost.[8]

Previous systematic reviews have assessed the effectiveness of various interventions for musculoskeletal disorders, including pharmaceutical therapies,[9–12] psychological-based therapies[13–16] and physical-based therapies, including manual therapy[17–19] and exercise.[16,20–24] These have all presented poor to moderate results in terms of effectiveness at improving pain and function, and have identified limitations in the quality of included trials when drawing conclusions.

There is a high level of uncertainty and lack of sufficient level 1 evidence on which to base treatment for people with musculoskeletal disorders. A systematic review of self-management interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain concluded that strong evidence existed that changes in the psychological factors, self-efficacy and depression were predictors of outcomes, irrespective of the intervention delivered, and strong evidence existed that positive changes in patients' pain catastrophising and physical activity were mediating factors.[25] Experimental studies have also demonstrated that stimulus context and the emotional response to pain affect the experience of pain,[26–28] and have led to the development of desensitisation interventions for chronic musculoskeletal disorders.[29–31]

It has been proposed that modern treatment therapies for chronic musculoskeletal pain and disorders should be designed around loading and resistance programmes targeting movements and activities that can temporarily reproduce and aggravate patients' pain and symptoms.[31–33]Pain does not correlate with tissue damage,[34] and psychological factors such as catastrophising and fear avoidance behaviours play an important role in the shaping of the physiological responses to pain, and therefore the development and maintenance of chronic pain.[35] It is thought that such an exercise programme could facilitate the reconceptualisation of pain by addressing fear avoidance and catastrophising beliefs within a framework of 'hurt not equalling harm'.[36,37] Through this, proponents support the prescription of exercises into pain for chronic musculoskeletal pain and disorders.[31,37,38] We define 'exercise into pain' as a therapeutic exercise where pain is encouraged or allowed.

No previous systematic reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of exercises into pain for chronic musculoskeletal pain. Therefore the object of this review was to compare the effect of exercises into pain compared with non-painful exercises on pain, function or disability in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain within randomised controlled trials (RCTs), specifically exercises that were prescribed with instructions for patients to experience pain, or where patients were told it was acceptable and safe to experience pain, and to compare any difference in contextual factors and prescription parameters of the prescribed exercise intervention.

This systematic review followed the recommendations of the PRISMA statement,[39] and was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, reference CRD42016038882).

An electronic database search was conducted on titles and abstract from inception to October 2016 on the following databases: the Allied and Complimentary Medicine Database, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, the Cochrane Library, Embase, Medline, SPORTDiscus and Web of Science. For the keywords and keywords search strategy used, please see Table 1. The database searches were accompanied by hand searches of the reference list of included articles, and the grey literature and ongoing trials were searched using the following databases: Open Grey, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, ClinicalTrials.gov and the bjsports-2016-097383 portfolio.

For inclusion, the studies had to meet the following criteria: adults recruited from the general population with any musculoskeletal pain or disorder greater than 3 months; participants with pain suggestive of non-musculoskeletal pain, for example, headache, migraine, bowel/stomach pain, cancer, fibromyalgia, chest pain, and breathing difficulties were excluded. Studies had to have a primary treatment arm of therapeutic exercises that was advised to be purposively painful, or where pain was allowed or tolerated. The comparison group had to use therapeutic exercises that were pain-free. Included studies were required to report pain, disability or function. Studies had to be full RCT published in English. Studies that were not randomised or quasi-random were excluded.

One reviewer (BES) undertook the searches. Titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (BES), with potential eligible papers retrieved and independently screened by two reviewers (BES and PH). Initial inclusion agreement was 81%, and using Cohen's statistic method the kappa agreement was k=0.47, which is considered 'fair to moderate' agreement.[40–42] All initial disagreements were due to intervention criteria, specifically the levels of pain during the therapeutic exercises in each intervention arm,[43–50] and were resolved through consensus. Three trials needed further information with regard to their control exercise to ascertain if they met the inclusion criteria, and all three were contacted.[51–53] All three responded with further information, and after discussion there was consensus to include two of the three trials.[51,52]

The following data were extracted from the included articles: trial design, participant information, intervention and control exercise, setting, follow-up periods and outcome data.[54] The data were independently extracted and transcribed to a standard table by one reviewer (BES), and then 25% of the data were independently checked by a second reviewer (PH). Effectiveness was judged in the short term (≤3 months from randomisation), medium term (>3 and<12 months) and long term (≥12 months), as recommended by the 2009 Updated Method Guidelines for Systematic Reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group.[55]

Each included study was appraised independently by two reviewers (BES and PH) for methodological quality using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised clinical trials.[56] The tool was originally developed in 2008, and updated in 2011, and is based on seven key bias domains:[57] sequence generation and allocation concealment (both within the domain of selection bias or allocation bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias).[56] For each domain the reviewers judged the risk of bias as 'high', 'low' or 'unclear'. Percentage agreement between the two reviewers for the individual risk of bias domains for the Cochrane risk of bias tool was 86%, with a kappa of κ=0.76, which is considered 'substantial or good',[40–42] and disagreements were resolved through consensus.

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to rate the overall quality of the body of evidence in each pooled analysis.[58] We did not evaluate the publication bias domain in this review as it is not recommended to assess funnel plot asymmetry with a meta-analysis of fewer than 10 trials.[59] A GRADE profile was completed for each pooled estimate. Where only single trials were available, evidence from studies with <400 participants was downgraded for inconsistency and imprecision and rated as low-quality evidence. Three reviewers assessed these factors for each outcome and agreed by consensus (BES, PH and TOS).

The quality of evidence was defined as the following: (1) high quality—further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; the Cochrane risk of bias tool identified no risks of bias and all domains in the GRADE classification were fulfilled; (2) moderate quality—further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and one of the domains in the GRADE classification was not fulfilled; (3) low quality—further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence and is likely to change the estimate; two of the domains were not fulfilled in the GRADE classification; and (4) very low quality—we are uncertain about the estimate; three of the domains in the GRADE classification were not fulfilled.[60,61]

Clinical heterogeneity was assessed through visual examination of the data extraction table on details related to participant characteristics, intervention, study design and process in the included studies. Based on this assessment, the reviewers judged there to be low clinical heterogeneity and accordingly it was appropriate to perform a meta-analysis where feasible. The primary outcome was a measure of pain, disability or function. As pain scores were reported on different scales, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD).[62] We a priori defined effect size interpretation as 0.2 for a 'small' effect size, 0.5 for a 'medium' effect size and 0.8 for a 'large' effect size, as suggested by Cohen (1988).[63] If data were not available, the associated corresponding author was contacted. Failing this, the mean and SD were estimated, assuming normal distribution, from medians and IQRs.[64]Statistical between-study heterogeneity was assessed with the I[22] statistic. We considered 0%–25% as low, 26%–74% moderate and 75% and over as high statistical heterogeneity.[65] When outcomes presented with low statistical heterogeneity, data were pooled using a fixed-effects model.[66]When analyses presented with moderate or high statistical heterogeneity, a DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was adopted.[67]

All data analyses were performed using the OpenMetaAnalyst software.[68]

A sensitivity analysis was performed for the primary and secondary analyses using only trials that presented with a low risk of bias.[56] In addition we carried out a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of studies where mean and SD were estimated from medians and IQRs, and outcome measures of pain were pooled scores set within pain domains from patient-reported outcome measures, for example, the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI).[69]

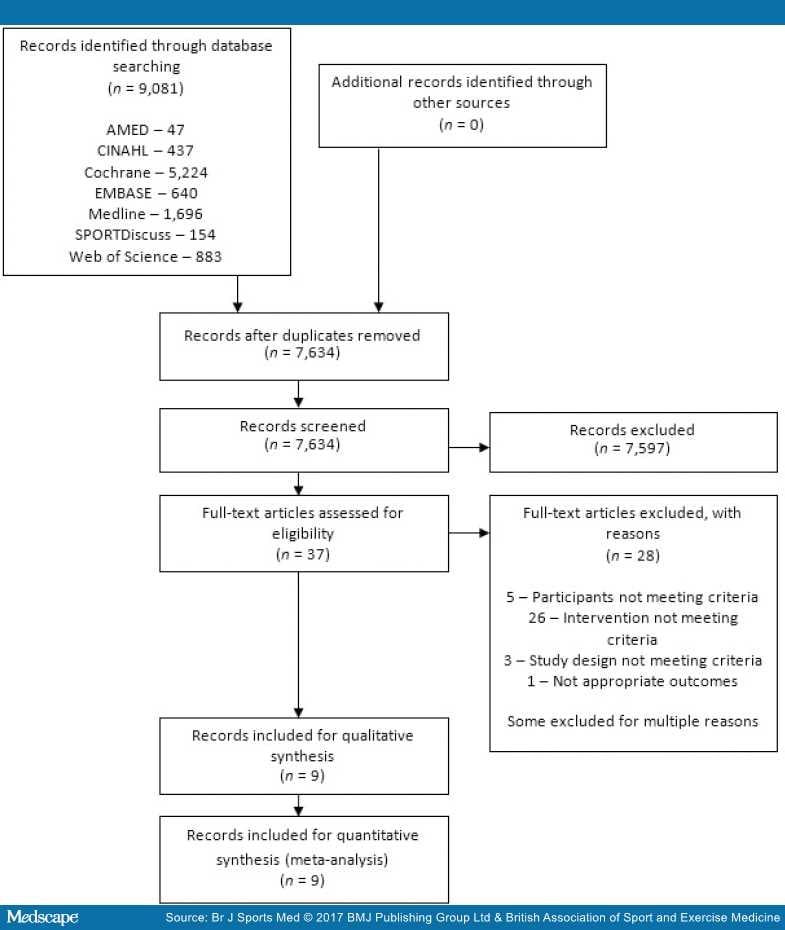

The search results are presented in Figure 1. The database search produced 9081 results, with no additional findings from reference list searches or unpublished searches. After duplicates were removed, 37 papers were appropriate for full-text review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

After full-text review, 28 articles were excluded, 5 were due to participants not meeting the criteria, 26 because the intervention did not meet the criteria, 3 because of study design not meeting criteria, and 1 due to inappropriate outcome measures. Some articles were excluded for multiple reasons. Therefore nine articles were included in the final review. Of the included articles, there were two occurrences of the same trial reporting different time points over two publications.[43,70–72]

A summary of the characteristics and main findings of the included trials can be found in Table 2.

The two occurrences of the same trial reporting different time points over two articles were analysed as single trials to prevent multiplicity in analyses.[43,70–72] All trials investigated home-based exercises, had a roughly even composition of women and men (46% women), with similar mean ages of participants (mean age 47, range 19–83). One trial included low back pain,[43,72] three included shoulder pain,[47,52,70,71] two included Achilles pain[73,74] and one included plantar heel pain.[51]

Three trials used a Visual Analogue Scale to measure pain,[43,70–72,74] two trials used the SPADI,[47,52] one used the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS),[73] and one used the Foot Function Index (FFI) including pain at worse and pain on first step on a numerical rating scale (0–10).[51]

Where pain outcomes were included within patient-reported outcome measures, these data were extracted.[47,52,73] Two trials that used the SPADI had insufficient data in the publication to complete a meta-analysis for pain,[47,52] and both were contacted and asked to supply pain domain data. Littlewood et al[52] replied and provided all the available data; however, Maenhout et al[47] did not respond. One trial reported outcomes in medians and IQRs,[74] and was contacted and asked for further data. They were unable to supply this, so the mean and SD were estimated assuming normal distribution.[64]

All seven trials recorded short-term follow-up of pain, four trials recorded medium-term follow-up of pain,[47,51,52,74] and five trials recorded long-term follow-up for pain.[43,51,52,70–73]

The two papers reporting long-term outcomes for the trials that reported different time points made reference to the short-term outcome papers with regard to design parameters; therefore, trial quality and bias were assessed accordingly.[43,70–72]

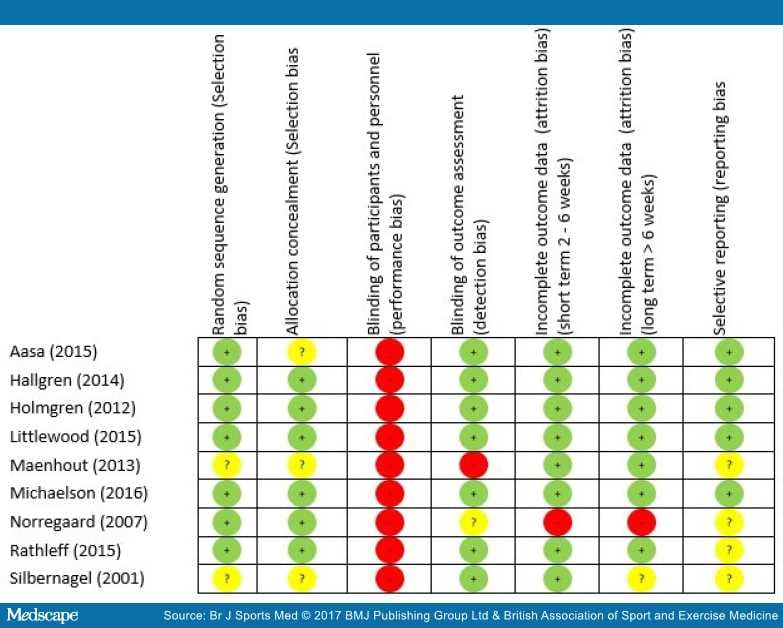

No trial had greater than three 'high risk' of bias scores for a domain (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary.

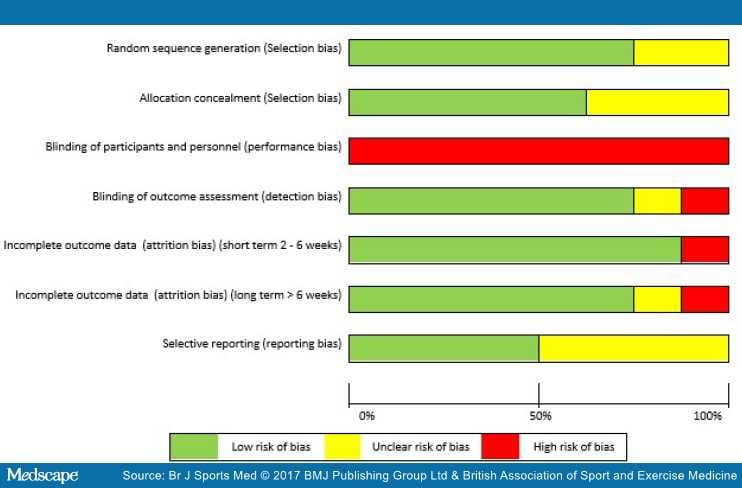

The greatest risk of bias was with the blinding of participants and personnel (100%) (Figure 3). The greatest amount of uncertainty was with regard to selective reporting bias, as many of the trials failed to include trials register details, or protocol details (44%).[47,51,73,74] Other common areas of bias with the included trials were with attrition bias, one trial failed to adequately describe attrition,[43] and two trials had large dropout rates;[52,73] however, Littlewood et al[52] received a 'low risk' score as their participant attrition was balanced across the intervention and control groups,[75] and an intention-to-treat analysis was performed. The risk of bias assessment tool highlights common trial write-up errors, with a number of papers failing to give an appropriate level of detail to adequately assess selection bias risk (33%).[43,47,74]

Figure 3.

Risk of bias graph.

Of the seven trials, six reported some form of patient-reported outcome measure of disability or function. One reported Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire,[43,72] one reported Constant-Murley and the Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand score,[70,71] two reported the SPADI,[47,52] one reported the KOOS,[73] and one reported the FFI.[51] With the exception of Rathleff et al,[51] there was clinically significant improvements in all outcomes, with no clear superiority. At 3-month follow-up for Rathleff et al,[51]the intervention group had a statistically significant lower FFI than the control group (p=0.016). At 1, 6 and 12 months, there were no differences between groups (p>0.34).

With regard to the parameters of pain in the exercise intervention the participants were advised to adhere to, each trial gave different instructions, the key differences being if pain was allowed[43,51,72,74] or recommended.[47,52,70,71,73] In addition other differences were if an acceptable level of pain measured on a pain scale was advised,[47,70,71,74] and a time frame for the pain to subside by, for instance, if the pain had to subside immediately,[43,51,52,72] by the next session[70,71] or by the next day.[47,73,74] Clinically significant improvements in patient-reported outcome measures were reported across all interventions and control exercises, and all time points. It is not clear from the data if one approach was superior to the others.

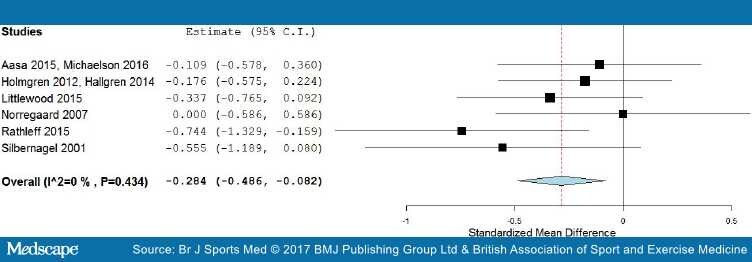

Short-term results. Six trials with 385 participants reported post-treatment effect on pain. Combining the results of these trials demonstrated significant benefit (SMD) of exercises into pain compared with pain-free exercises for musculoskeletal pain in the short term, with a small effect size of −0.28 (95% CI −0.49 to −0.08; Figure 4). Statistical heterogeneity was negligible, I2=0%. The quality of evidence (GRADE) was rated as 'low quality' due to trial design and low participant numbers (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of exercises into pain versus pain-free exercises—short term. Negative values favour painful intervention, whereas positive favour pain-free.

For sensitivity analysis in the short term, we repeated the meta-analysis, removing two trials that used a patient-reported outcome measures index and had high dropout rates,[52,73] and the Silbernagel et al[74] trial where the mean and SD were estimated from medians and IQRs. The results of the data synthesis produced very similar results, with a small effect size of −0.27 (95% CI −0.54 to −0.05), with low statistical heterogeneity of I2=22%. The quality of evidence (GRADE) was rated as 'moderate quality' due to low participant numbers (Table 3).

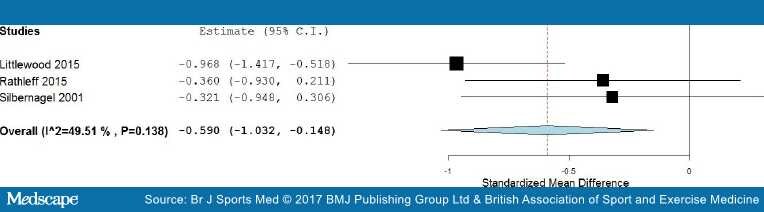

Medium-term results. In the medium-term follow-up, meta-analysis demonstrated significant benefit (SMD) for exercises into pain compared with pain-free exercises for musculoskeletal pain, with a medium effect size of −0.59 (95% CI −1.03 to −0.15) (see Figure 5). The statistical heterogeneity was moderate, I2=50%. The quality of evidence (GRADE) was rated as 'low quality' due to trial design and low participant numbers (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of exercises into pain versus pain-free exercises—medium term. Negative values favour painful intervention, whereas positive favour pain-free.

Sensitivity analysis was not possible for medium-term results as two trials were excluded, one for using a patient-reported outcome measures index,[51] and one due to means and SD being estimated from medians and IQRs.[74] The one remaining trial showed no significant difference in the medium term.[51] The quality of evidence (GRADE) was rated as 'low quality' due to it being only from a single trial (Table 3).

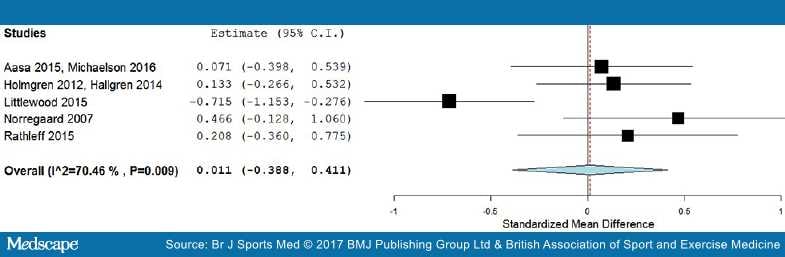

Long-term results. In the long term follow-up, meta-analysis demonstrated no statistical difference between exercises into pain and pain-free exercises, with an effect size of 0.01 (95% CI −0.39 to 0.41) (Figure 6). The statistical heterogeneity was high, I2=70%. The quality of evidence (GRADE) was rated as 'very low quality' due to trial design, heterogeneity and low participant numbers (Table 3).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of exercises into pain versus pain-free exercises—long term. Negative values favour painful intervention, whereas positive favour pain-free. AMED, Allied and Complimentary Medicine Database; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

For sensitivity analysis in the long term, we repeated the meta-analysis, removing the two trials that used a patient-reported outcome measures index.[52,73] The results of the data synthesis found no statistical difference between exercises into pain and pain-free exercises, with an effect size of 0.13 (95% CI −0.14 to 0.40). The statistical heterogeneity was negligible, I2=0%. The quality of evidence (GRADE) was rated as 'moderate quality' due to low participant numbers (Table 3).

There was a significant short-term benefit for exercises into pain over pain-free exercises for patient-reported outcomes of pain, with a small effect size and moderate quality of evidence. There appears to be no difference at medium-term or long term follow-up, with the quality of the evidence rated as moderate to low.

Traditionally, healthcare practitioners have been reluctant to encourage patients to continue with exercise into pain when they are treating chronic musculoskeletal pain,[76] with some research suggesting clinicians' fear being the primary deterrent.[77] The results of our systematic review show that there does not appear to be a scientific basis for this fear in relation to outcome measures of pain, and also potentially function and disability. This is an important point when considering what advice is given on any short-term exacerbations of musculoskeletal pain during physical activity or exercise by healthcare practitioners, particularly when physical inactivity is one of the 10 leading risk factors for death worldwide,[78] and when an estimated €1.9 billion a year in healthcare and €9.4 billion a year in economic costs in the UK are attributable to physical inactivity.[79]

A theoretical rationale for a positive response to exercises into pain is the positive impact on the central nervous system.[31,37] Specifically, the exercise addresses psychological factors such as fear avoidance, kinesiophobia and catastrophising, and is set within a framework of 'hurt not equalling harm', thus, in time, reducing the overall sensitivity on the central nervous system, with a modified pain output.[31,37] The exercise-induced endogenous analgesia effect is thought to occur due to a release of endogenous opioids and activation of spinal inhibitory mechanisms.[80–84] However, a recent systematic review has established that no firm conclusions could be reached about pain modulation during exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain.[85] Indeed one experimental study has shown a dysfunction of endogenous analgesia in patients with musculoskeletal pain,[86] and therefore exercising non-painful body parts with patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain has been recommended.[87] However, it is worth noting that empirical data within this field are greatly lacking, and this systematic review shows that painful exercises may even improve the clinical outcomes. Additionally, exercise prescription in the included trials was primarily based on strength and conditioning principles, with the exception of Littlewood et al,[52] suggesting a tissue-focused approach, and therefore could still have been giving a 'hurt is harm' message to the majority of participants.

Significant improvements in patient-reported pain can be achieved with a range of contextual factors, such as varying degrees of pain experiences and postrecovery time for therapeutic exercise. In addition to the aspect of pain, an important difference between the intervention arm and the control arm is the higher loads, or levels of resistance, employed with the exercises into pain, and it is unknown if the difference in responses can be attributable to these two elements of the different exercise programmes. Research has shown a 'dose response' to exercise for musculoskeletal pain—the more incremental exercise (with appropriate recovery period) a person does the greater his/her improvements in pain;[88–90] the short-term benefits of exercises into pain over pain-free exercises could be explained by this dose effect, or response to load/resistance. However to our knowledge the optimal 'dose' of therapeutic exercise for musculoskeletal pain has not been established. Furthermore, little is known if it is possible or appropriate to identify individuals most suitable to exercise interventions.

Our review only investigated patient-reported outcome measures of pain and function/disability. It has been hypothesised that exercise therapy, where it has been advised that the experience of pain is safe and allowed, may address other patient-reported outcome measures—fear avoidance, self-efficacy and catastrophising beliefs[37,38] —and therefore may lead to improvements in function, quality of life and disability, despite pain levels. Unfortunately none of the trials included in this review recorded the level of pain patients actually experienced during their exercise programme, preventing any detailed attempt to fully explain any mechanisms of effect. This aspect of exercise prescription clearly warrants further investigation in relation to chronic musculoskeletal pain. Any future trials should consider the role of pain with exercises and clearly define the parameters employed to ensure translation of findings into practice and further evaluation of optimal 'dosage'.

We chose not to perform subgroup analyses by anatomical region and/or tissue structures. The labelling of musculoskeletal structures as sources of pain has been debated for many years, with polarising opinions.[91,92]However, the diagnostic labelling of patients into tissue-specific pathology characteristically suffers from poor reliability and validity.[93–98] A strength of this review is that despite the trials including subjects suffering from musculoskeletal pain at different body locations, there exists low statistical heterogeneity at short-term follow-up and for the sensitivity analyses carried out.

The overall quality of the included papers can be considered relativity high, with only three domains in the Cochrane risk of bias tool (disregarding blinding of participants) demonstrating clear risk of bias across all domains for all trials. However taking into account other factors assessed with the GRADE analysis, the quality of the evidence was rated as moderate to low. Therefore our results can be considered to have moderate to low internal validity, with future research likely to alter our conclusions.

The main source of bias within the included trials were blinding; no trial blinded the participants. Knowledge of group assignment may affect participants' behaviour, for example with patient-reported outcome measures such as pain scales or compliance with therapy interventions.[99]However, it is accepted that blinding in physiotherapy and physical intervention trials is difficult to achieve.[24]

Another limitation of the included trials is the high level of attrition suffered by some of the trials in both treatment arms. For example Littlewood et al[52]suffered from 51% dropout at 12-month follow-up. A high level of attrition can overestimate the treatment effect size and could bias the results of our meta-analysis. However, we minimised the risk of bias on our results by conducting a sensitivity analysis on trials with a large dropout, identified using the Cochrane risk of bias tool and assessed level of evidence using the GRADE classification.

For pragmatic reasons one reviewer screened titles and abstracts. An extensive literature search was carried out, with two reviewers independently screening full texts for inclusion, and a sample of the data extraction independently verified. Additionally an attempt was made to retrieve unpublished trials; however, it may be that not all trials were retrieved, particularly considering we did not search for papers published in languages other than English and US spelling was used in the search terms. This review excluded trials where participants had a diagnosis of more widespread pain disorders like fibromyalgia.

The results of this systematic review indicates that protocols using exercises into pain offer a small but significant benefit over pain-free exercises in the short term, with moderate quality of the evidence for outcomes of pain in chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. There appears to be no difference at medium-term or long-term follow-up, with moderate to low quality of evidence, demonstrating pain need not be ruled out or avoided in adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain.