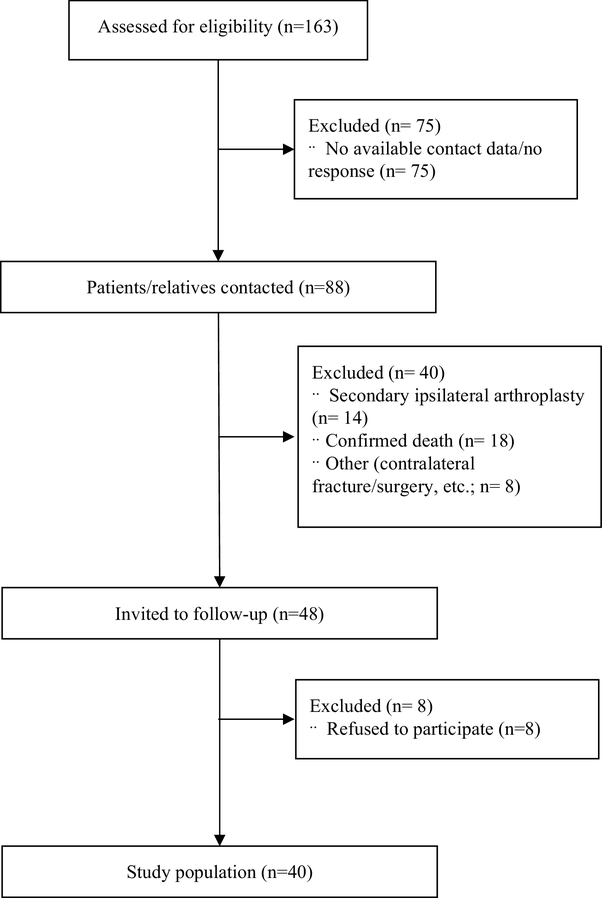

Shortening of the femoral neck following internal fixation of femoral neck fractures is a known phenomenon. However, the available literature describes incidence and extent of shortening in these patients of only up to 2 years [2, 10, 11]. Furthermore, these studies mainly did not focus on young patients, who due to higher functional demands, more likely suffer from shortening and LLD compared to elderly patients. Previous studies have shown that also younger patients are prone to experience shortening after fractures of the proximal femur [11, 12, 13]. Advocators of prosthetic replacement as treatment of femoral neck fractures often use shortening as argument against internal fixation of these fractures. We showed that following internal fixation of femoral neck fractures shortening is present in most cases, with a prevalence of 92.5% at 3 months postoperatively. In 32.5% of patients, femoral neck shortening of more than 10 mm was seen. Confirming our data, Zlowodzki et al. reported a prevalence of 30% of femoral neck shortening of more than 10 mm [10]. Also, median femoral neck shortening of 7 mm and median femoral shortening of 5 mm 3 months postoperatively were comparable with the available literature [2, 10]. Our data indicate that the fracture angle used in Pauwels classification might be of relevance for the extent of femoral neck shortening. We found that higher fracture angles were associated with larger extent of femoral neck shortening. Furthermore, weight was correlated to the extent of shortening. Both findings confirm results provided by Zielinski and colleagues. They showed that aside from Pauwels classification, also BMI and age were associated with shortening [2]. In our study a correlation with age was not observed. We, therefore, assume that in non-geriatric patients with lower rates of osteoporosis the correlation of age with femoral neck shortening might be negligible.

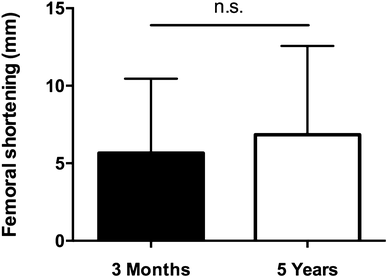

Since the available literature focused on shortening up to 2 years follow-up, we were interested whether incidence and extent of shortening increased in the mid-term follow-up and if there was a correlation with early shortening. The incidence of femoral neck shortening and femoral shortening was comparable at postoperative and invited follow-up. This suggests that shortening after femoral neck fractures in non-geriatric patients occurs mainly during the initial 3 months. As expected, the amount of initial shortening correlated with LLD at invited follow-up.

There is still the ongoing discussion, whether primary arthroplasty or internal fixation is the better treatment option in younger patients [4, 5, 6, 9, 13, 14, 15]. While internal fixation tries to preserve the joint, there is a significant risk of implant failure, revision surgery, and avascular femoral head necrosis following femoral neck fractures and internal fixation. Up to 27% salvage arthroplasty were reported in a previous study [9]. We observed a comparatively low rate of secondary hip replacement of 16%, which might be explained in part by the relatively high number of patients lost to follow-up. However, Slobogean et al. reported a re-operation rate of 14% due to avascular head necrosis, which is comparable to our findings [16]. Another study found an even lower rate with around 7% of avascular head necrosis [17]. Here presented data support internal fixation, which should be the primary treatment in young patients with femoral neck fractures. Even in cases of necessary secondary arthroplasty, potential gain in time can decrease chance of revision surgery after prosthetic replacement.

Importantly and further supporting primary internal fixation, we did not observe statistical significant differences in functional outcome in dependence of femoral shortening at 5-year follow-up. Only a trend towards lower HHS in patients experiencing more than 10 mm of femoral shortening was observed with still excellent scores in this sub-group. Other studies have shown that shortening was linked to impaired functional outcome [2, 10]. In these studies, however, the group of patients with larger extent of shortening were older compared to patients with less shortening. This potential bias might also have caused lower number in the HHS. Also, overall our patients were younger with potentially higher capacity to compensate for shortening.

Sub-group analysis revealed no relevant differences in terms of shortening and functional outcome. However, comparison between these two fixation methods has to be dealt with caution due to small patient numbers. Siavashi and colleagues found a lower rate of fixation failure of DHS compared to cancellous screws for the treatment of femoral neck fractures [18]. Another study failed to show significant differences between both treatment options [17]. Recently, the FAITH trial reported comparable outcomes for fracture fixation with the DHS and cannulated screws with small advantages in sub-group analyses favouring treatment with DHS [19].

Our postoperative mobilisation scheme consists of 3 months non-weight bearing if tolerated following internal fixation of femoral neck fractures. The rationale behind the non-weight-bearing mobilisation was to reduce pressure at the fracture site potentially reducing shortening and limiting the risk of AVN. However, we found a high incidence rate of femoral shortening and LLD in our patients. Furthermore, Wang et al. reported no correlation between postoperative mobilisation scheme and the risk for AVN [20]. Taken together, following these findings our postoperative non-weight-bearing regime has to be questioned.

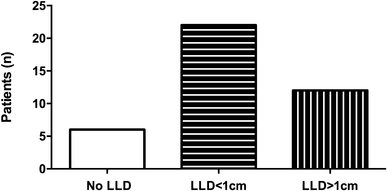

Aside from impaired hip function, shortening with concomitant untreated LLD is a known predisposing factor for osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, and spine causing pain and disability [21]. In the overall population, LLD rates between 3 and 15% have been described [21]. In our study, we found a high overall rate of LLD of 85%, 5.5 years after surgery. Our data suggest that especially young patients benefit from long-term clinical follow-up.