Electronic searches conducted on June 16, 2017 retrieved 1611 records after removing duplicates. After the screening of titles and abstracts, we assessed 61 full texts against our inclusion criteria. Of these, we excluded 46 full texts because they were: not the most recent guideline issued (n = 19), not guidelines (n = 15), not targeted at a multidisciplinary audience (n = 10), and not in a language where we could obtain a translation (n = 2). Finally, 15 clinical practice guidelines [1, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 15, 20, 24, 27, 30, 31, 32] for the management of LBP were included from the following countries: Africa (multinational), Australia, Brazil, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, Philippine, Spain, the USA, and the UK.

Six guidelines [1, 7, 11, 20, 26, 28] (40%) provided recommendations for patients with acute, subacute, and chronic LBP (i.e., Canada, Finland, Mexico, Philippine, Spain, and the USA), two guidelines [15, 31] (13%) focussed on acute and chronic LBP (i.e., Malaysia and the Netherlands), three guidelines [9, 25, 30] (20%) focussed on acute LBP (i.e., Australia, and Denmark), and one guideline [3] (7%) focussed on chronic LBP (i.e., Brazil). In addition, three guidelines [10, 24, 32] (20%) provided recommendations regardless of the duration of symptoms (i.e., Africa, Belgium, Germany and the UK). Therefore, ten guidelines contained recommendations for patients with acute LBP, six guidelines contained recommendations for patients with subacute LBP, and nine guidelines contained recommendations for patients with chronic LBP.

Three guidelines [1, 11, 28] defined acute LBP as less than 4 weeks duration, two guidelines [6, 26] specified less than 6 weeks duration and four guidelines [15, 25, 30, 31] defined acute LBP as less than 12 weeks duration. The Canadian guideline [7] defined acute and subacute LBP as less than 12 weeks duration but without specifying the cutoffs for each one. All guidelines defined chronic LBP as more than 12 weeks’ duration.

Diagnostic recommendations

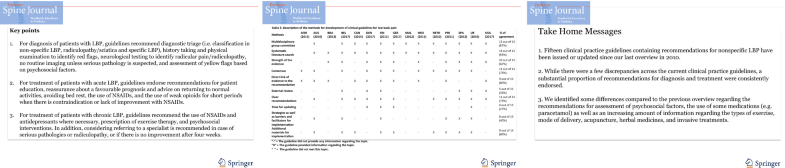

Table

1 describes the recommendations regarding diagnosis endorsed by each clinical practice guideline, and “supplementary material: Appendix 1” details these recommendations. Fourteen guidelines provided at least one recommendation regarding diagnosis of patients with LBP. The American guideline [

28] did not provide any recommendation regarding diagnosis because the committee group was instructed to make only recommendations for treatment of LBP.

Table 1

Recommendations of clinical guidelines for diagnosis of low back pain

Recommendations for diagnostic triage were found in 13 guidelines. Over half of guidelines [

1,

7,

24,

25,

26,

31,

32] (7 out of 13; 54%) recommend diagnostic triage to classify patients into one of three categories: non-specific LBP, radiculopathy/sciatica or specific LBP. Almost half of the guidelines [

3,

9,

10,

11,

15,

20] (46%) recommend the classifications of non-specific LBP and specific LBP without distinguishing the group of patients with radicular pain/radiculopathy. Most guidelines [

1,

7,

11,

15,

20,

24,

25,

26,

31,

32] (10 out of 12; 83%) recommend history taking and physical examination to identify patients with specific conditions as the cause of the LBP. Box

1 describes the red flags endorsed by most clinical practice guidelines to identify serious conditions in the assessment. In addition, most guidelines [

1,

7,

11,

15,

25,

26,

31] (7 out of 9; 78%) recommend neurologic examination to identify radicular pain/radiculopathy including straight leg raise test [

1,

7,

15,

26,

32] and assessment of strength, reflexes, and sensation [

1,

11,

15]. Only three guidelines [

11,

15,

26] (3 out of 12; 25%) recommend an assessment that also includes palpation, posture assessment, and spinal range of movement testing.

Box 1

Red flags endorsed by most clinical practice guidelines

All guidelines recommend against the use of routine imaging for patients with non-specific LBP. Most guidelines [1, 7, 9, 10, 11, 25, 30] (7 out of 12; 58%) recommend that imaging should only be considered if red flags are present. In addition, five guidelines [1, 7, 10, 24, 32] (42%) suggest imaging when the results are likely to change or direct the treatment (e.g., invasive treatments), and two guidelines (17%) recommend imaging if pain persists beyond 4 to 6 weeks [7, 26].

Twelve guidelines contain recommendations for assessment of psychosocial factors, or yellow flags, to identify patients with poor prognosis and guide treatment. Most guidelines [

1,

7,

9,

11,

15,

20,

26,

31] (8 out of 12; 67%) recommend the assessment based on a list of yellow flags reported in the guideline. Box

2 provides these yellow flags endorsed by most clinical practice guidelines. Four guidelines [

10,

24,

25,

32] (33%) recommend assessment using validated prognostic screening tools (e.g., STarT Back and Orebro) which combine a number of yellow flags. The Danish guideline [

30] recommends against targeted treatment for a subgroup of patients with specific prognostic factors. Regarding the optimal timing to assess yellow flags, most guidelines [

7,

10,

11,

15,

24,

25,

32] (7 out of 12; 58%) recommend assessment during the first or second consultation.

Box 2

Yellow flags endorsed by most clinical practice guidelines

Treatment recommendations

Table

2 provides the recommendations regarding treatment endorsed by each clinical practice guideline, and “supplementary material: Appendix 2” details these recommendations. All guidelines provided at least one recommendation regarding the treatment of LBP.

Table 2

Recommendations of clinical practice guidelines for treatment of low back pain

Recommendations regarding bed rest were provided in 12 guidelines. Most guidelines [7, 9, 11, 15, 25, 30, 31] (7 out of 11; 64%) recommend avoiding bed rest for patients with acute LBP, and four guidelines [1, 10, 20, 26] (36%) recommend for any duration of symptoms. The only exception was the Belgian guideline [32] (8%) which notes an absence of evidence on the benefits or harms of bed rest when used in the short term.

Recommendations on reassurance or advice for patients with non-specific LBP were identified in 14 guidelines. Most guidelines (7 out of 12; 58%) recommend advice to maintain normal activities for patients with acute LBP [1, 7, 10, 15, 25, 30, 32], and some guidelines (42%) recommend the same advice for patients with any duration of symptoms [20, 24, 26, 31, 32]. In addition, most guidelines (10 out of 14; 71%) recommend reassuring the patient that LBP is not a serious illness regardless of the duration of symptoms or reassuring patients with acute LBP of the favorable prognosis [7, 15, 20, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 32].

The recommendations for the prescription of medication vary depending on the class of medication and symptom duration. Most guidelines (14 out of 15; 93%) recommend the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for patients with acute and chronic LBP considering the risk of adverse events (e.g., renal, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal) [1, 3, 7, 15, 24, 25, 26, 28, 32]. For paracetamol/acetaminophen, while most guidelines recommend in favor of this medication [1, 3, 7, 11, 15, 20, 26, 31] (8 out of 14; 57%), five guidelines [10, 24, 27, 30, 32] (36%) advise against the use of paracetamol. The Australian guideline [25] recommends the use of paracetamol but advises that clinicians and patients should be made aware that the medicine might not be effective. Most guideli

nes (13 out of 15; 87%) recommend weak opioids [1, 15, 24, 26, 31, 32] for short periods [3, 7, 10, 20, 31, 32], if there is no improvement with NSAIDs or other treatments. The guidelines recommend opioids for acute LBP [1, 7, 9, 10, 11, 24, 26, 32] (8 out of 13; 61%), chronic LBP [1, 3, 10, 27, 31] (38%), and for any symptom duration [15, 20] (23%). For antidepressants, most guidelines (6 out of 8; 75%) recommend its use for patients with chronic LBP where necessary [1, 3, 7, 11, 26, 28]. For muscle relaxants, most guidelines [1, 7, 11, 20, 26, 28] (6 out of 11; 54%) recommend this medication for acute LBP [1, 26, 28] (3 out of 6; 50%), chronic LBP [1, 7] (33%), and for any symptom duration [11, 20] (33%). In contrast, five guidelines (5 out of 11; 45%) recommend against muscle relaxants [3, 9, 10, 31, 32]. Two guidelines mentioned the use of herbal medicine for LBP (2 out of 15; 13%); one recommends its use for patients with chronic LBP [7], but the other recommends against it for any type of LBP [10].

Recommendations for referral to a specialist were found in 13 guidelines. Most guidelines [1, 7, 15, 20, 24, 26, 30, 32] (9 out of 13; 69%) recommend referral to a specialist in cases where there is suspicion of serious pathologies or radiculopathy. In addition, most guidelines [7, 9, 10, 20, 25, 30, 31] (7 out of 13; 54%) recommend referral to a specialist if there is no improvement after a time period that ranges from 4 weeks to 2 years.

Recommendations on invasive treatments (e.g., injections, surgery, and radiofrequency denervation) for non-specific LBP were identified in 8 guidelines. Of these, five guidelines (5 out of 8; 62%) recommended against the use of injections for non-specific LBP [7, 10, 24, 25, 31]. In addition, four guidelines [7, 10, 24, 25] (50%) recommend against surgery or radiofrequency denervation [7, 10, 25, 31] (50%) for non-specific LBP. In contrast, three guidelines [1, 24, 32] (37%) recommend radiofrequency denervation for chronic LBP; however, two guidelines [24, 32] (25%) recommended only in strict circumstances such as lack of improvement after conservative treatment, a positive response to a medial branch nerve block, and moderate to severe back pain. Some guidelines recommend surgery for chronic LBP due to disk herniation or spinal instability [1, 15] and common degenerative disorders [1].

Recommendations for multidisciplinary rehabilitation were identified in nine guidelines. Most guidelines (9 out 11; 90%) recommend multidisciplinary rehabilitation for patients with chronic LBP [7, 10, 11, 15, 24, 25, 26, 28, 32]. One guideline [20] recommends multidisciplinary rehabilitation for any duration of symptoms, and one guideline [31] recommends if there is no improvement after monodisciplinary approach.

Recommendations for psychosocial strategies were found across eleven guidelines. Most guidelines (10 out of 11; 91%) endorse the use of a cognitive behavior approach [7, 10, 11, 20, 24, 25, 26, 28, 31, 32]. In addition, most guidelines (9 out of 11; 82%) recommend these therapies for patients with chronic LBP [7, 10, 15, 20, 24, 26, 28, 31, 32] with some of them recommending only if psychosocial factors are identified [15, 24, 31, 32].

All clinical practice guidelines provided recommendations for exercise therapy. Most guidelines (10 out of 14; 71%) recommend exercise therapy for patients with chronic LBP [1, 3, 7, 11, 15, 20, 26, 28, 31]. Noteworthy, we identified great discrepancy in the type of exercise program (e.g., aquatic exercises, stretching, back schools, McKenzie exercise approach, yoga, and tai-chi) and mode of delivery (e.g., individually designed programs, supervised home exercise, and group exercise). Guidelines provided inconsistent recommendations on exercise therapy for acute LBP.

The recommendations for spinal manipulation and acupuncture vary across clinical practice guidelines. Eleven guidelines provided recommendations for spinal manipulation, and nine guidelines recommended its use. Most guidelines (6 out of 9; 66%) recommend spinal manipulation for acute LBP, but there are some discrepancies on the indications. The guidelines recommend spinal manipulation in addition to usual care [30], if there is no improvement after other treatments [7, 31], or in any circumstance [10, 28]. Three guidelines [15, 24, 32] (33%) recommend spinal manipulation as a component of a multimodal or active treatment program for patients with any symptom duration. Three guidelines (33%) recommend spinal manipulation as a component of a multimodal treatment program [10] or in any circumstance for chronic LBP [28]. In contrast, two guidelines recommend against spinal manipulation for acute LBP [9] or chronic LBP [31].

Similarly, the recommendations for acupuncture were inconsistent. Four guidelines [1, 7, 10, 28] recommend the use of acupuncture. Of these, three guidelines recommend acupuncture for patients with acute and chronic LBP [1, 28]. One guideline [7, 10] recommends acupuncture as an adjunct of an active rehabilitation program for patients with chronic LBP. Four out of eight guidelines do not recommend acupuncture [9, 24, 30] (37%) or state that acupuncture should be avoided [25] (13%).

Methods of development of the clinical practice guidelines

Table

3 provides the methods of development and implementation reported by each clinical practice guideline, and “supplementary material: Appendix 3” details these methods. Most guidelines [

1,

7,

10,

11,

15,

20,

24,

25,

26,

28,

30,

31,

32] were issued by a multidisciplinary group including healthcare professionals such as primary care physicians, physical and manual therapists, chiropractors, psychologists, orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and radiologists. The African guideline [

9] was developed by a medical group, and the Brazilian guideline [

3] was developed by an association comprised of physiatrists.

Table 3

Description of the methods for development of clinical guidelines for low back pain

Most guidelines based their recommendations on systematic literature searches of electronic databases and previous version of guidelines (14 out of 15; 93%) [1, 3, 7, 10, 11, 15, 20, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 32], evaluated the strength of the evidence (10 out of 15; 67%) [1, 3, 10, 11, 20, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 32], and used consensus in the working group when necessary (11 out of 15; 73%) [1, 9, 10, 11, 20, 24, 25, 26, 30, 31, 32]. In addition, most guidelines gave direct links between the recommendations and the evidence (9 out of 15; 60%) [1, 3, 7, 9, 10, 11, 25, 30] and provided clear and specific recommendations (11 out of 15; 73%) [1, 7, 10, 20, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 32]. In contrast, few guidelines provided sufficient information regarding their external review process (5 out of 15; 33%) [20, 24, 28, 30, 32] and the time frame for updates (4 out of 15; 27%) [10, 24, 26, 30]. Where it was reported, this ranged from 2 to 5 years.

Most guidelines were available on the website of the participating organization, and some guidelines [3, 10, 11, 28, 30] were published in scientific journals. Most guidelines (9 out of 15; 60%) were accompanied by additional materials for dissemination [1, 7, 10, 20, 24, 25, 26, 31, 32] such as different versions for patients and clinicians, a care pathway, a summary version, an interactive flowchart, or videos. A few guidelines (6 out of 15; 40%) reported strategies or the barriers and facilitators for implementation [1, 20, 24, 26, 32].

Changes in recommendations over time

Few changes were identified in the recommendations on diagnosis of non-specific LBP compared to the previous guidelines. Currently, most guidelines still recommend the assessment of psychosocial factors based on yellow flags at the first or second consultation. Of note, an increasing proportion (33%) of guidelines are recommending the use of validated prognostic screening tools (e.g., STarT Back screening tool or Örebro).

Some recommendations changed compared to the previous guidelines for the use of medications for non-specific LBP. Our 2010 overview found a hierarchical order including paracetamol as the first choice and NSAIDs as the second choice. In this review, we identified that most guidelines recommend only the use of NSAIDs as the first choice for any duration of symptoms. Of note, most current guidelines recommend antidepressants, where necessary, for chronic LBP which was not endorsed by the previous guidelines. The recommendations regarding the NSAIDs and antidepressants were consistent across guidelines included in this review.

We also identified more details on the recommendations regarding some approaches compared to the past guidelines. The current clinical practice guidelines suggest some types of exercise and modes of delivery for patients with chronic LBP compared to the previous guidelines which only noted the preference for using intensive training. We also found recommendations regarding some approaches in this review which were not previously cited in past guidelines such as the use of herbal medicines, acupuncture, and invasive treatments. However, the recommendations regarding these approaches were inconsistent or cited in a small proportion of guidelines (i.e., less than 50% of the guidelines).