This study aimed to describe the clinical course of cervical radiculopathy for those patients who are managed conservatively and to derive prognostic models to identify patients at risk for poor recovery.

Clinical course

According to the findings regarding perceived effect, approximately half of the patients indicated to be recovered at 6 and 12 months. Similar proportions were observed for neck and arm pain recovery. Although the mean reported pain intensities (3/10 NRS) and level of disability (2/10 NRS) were fairly low at 12 months, the variability between patients was rather large. Approximately 20% of patients still experienced high-intensity pain and high level of disability at 6 months, and ~ 15% at 12 months. In addition, ~ 20% of patients took medication typically prescribed for moderate to severe (neuropathic) pain at 6 months, and ~ 10% at 12 months (opioids, antidepressants and anti-epileptics). It is noteworthy that recovery, pain and disability levels were similar at 6 and 12 months, indicating that further improvement between 6 and 12 months was limited.

A recent systematic review summarizing two studies revealed that most improvement occurs in the first 4–6 months and that 83% of patients recovered completely within 2–3 years [7]. In our study, the long-term recovery (12 months) was less favorable, possibly because we included a larger proportion of patients with a longer history of symptoms. This seems a plausible explanation, since longer duration of symptoms was associated with poor recovery in our multivariable prognostic models.

Prognosis

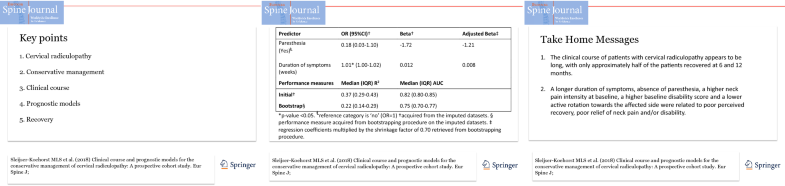

The multivariable logistic regression analyses generated plausible prognostic models containing a combination of predictors that are commonly captured and easily obtainable in clinical practice. A longer duration of symptoms, absence of paresthesia, a higher neck pain intensity at baseline, a higher baseline disability score and a lower active rotation toward the affected side were related to poor perceived recovery, poor relief of neck pain and/or disability at 12 months. After bootstrapping, all prognostic models showed an adequate predictive performance with modest diagnostic accuracy and explained variance. The results indicate that the models may potentially be useful to identify patients with a less favorable prognosis.

Some of the identified variables have previously been identified as univariable predictors for other musculoskeletal conditions, and some may be more unique to cervical radiculopathy [16, 23]. High initial pain intensity and a long duration of symptoms are known to be predictive of a poor recovery in various musculoskeletal disorders [16]. High levels of initial disability have been associated with poor recovery in musculoskeletal disorders [16] and lumbar radiculopathy [23]. For lumbar radiculopathy, sensory changes, including paresthesia, were not associated with outcome [23], whereas our study revealed that presence of paresthesia at baseline was associated with a lower chance of a poor perceived recovery. This seems counterintuitive. However, based on the finding that the presence of paresthesia decreased from 82% of patients at baseline to 42% at 12 months, one could argue that resolution of paresthesia may be an important factor in perceived recovery. The association between a larger active rotation toward the affected side and a reduced risk of persistent disability was in line with prior research indicating that movement restrictions are negative prognostic factors for musculoskeletal disorders [16].

It would have been informative to perform subgroup analyses based on type of nerve root compression (i.e., disk herniation, stenosis or a combination), or more specifically on the level, type and site of the disk herniation. However, we were unable to perform subgroup analyses because of the small dataset for these items. We recommend that the characteristics of the nerve root compression are taken into account in future research into the prognosis of cervical radiculopathy.

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. Possible predictors were selected based on theoretical plausibility. Given the finite number of possible predictors that can be considered, we had to limit the selection to the most plausible predictors for each outcome variable. Since little is known about the prognostic factors for cervical radiculopathy, we made a priori assumptions about which predictors would be most valuable to determine the prognosis. We focused on possible predictors that were widely available to health practitioners in various settings. We therefore selected predominantly signs and symptoms as possible predictors. Including other factors, such as results from electrodiagnostic test or imaging, or psychosocial factors (e.g., anxiety and depression) may have yielded different results.

The nature of physiotherapy (e.g., type of exercises) and manual therapy (e.g., type of mobilization) were not recorded in detail. Hence, we cannot draw conclusions about the influence of different types of interventions on the prognosis. Given that studies of the effectiveness of physiotherapy and manual therapy in patients with cervical radiculopathy have shown comparable results, we assume that the influence of specific characteristics of the treatment on prognosis would be limited [5, 24].

To resolve the issue of missing data, we performed multiple imputations on the predictor variables with missing data and the outcome variables. Multiple imputation is used increasingly to account for missing data, and it is reported to be more valid than using complete-case analysis only [13, 25, 26].

Due to the strict diagnostic criteria we used for cervical radiculopathy, the number of patients we could recruit in the available time frame was smaller than anticipated. This resulted in a lower number of cases per event than preferred [13]. However, we accounted for possible overfitting by combining the multiple imputations with a strict bootstrap procedure [27]. In line with expectations, the bootstrap procedure showed a shrinkage factor of approximately 0.70 in all models. Consequently, the diagnostic accuracy and the explained variance were slightly lower in all models. Given the multiple imputation methods used and the internal validation procedure, we believe that these results adequately reflect the prognostic value of the models and correct for the optimism in the initial models. However, considering the smaller dataset to derive the models and the relatively large amount of missing data, it is important that these findings are validated in a larger external dataset. Until these prognostic models have been confirmed, the results should be interpreted with caution.