Nonspecific low back pain that persists and is unresponsive to treatment (CNSLBP) constitutes the largest part of the health and socioeconomic impact of this problem [1]. However, risk-based subgroupings give little insight into how individual cases should be managed when treatment has failed [2]. While important advances have been made in explaining the mechanisms involved in central pain modulation in CNSLBP patients, there have been few in relation to the biomechanical factors driving peripheral pain stimuli [3]. Thus, health professionals often have difficulty in identifying the biological mechanisms in CNSLBP and as a result may rely overly on psychosocial management [3, 4].

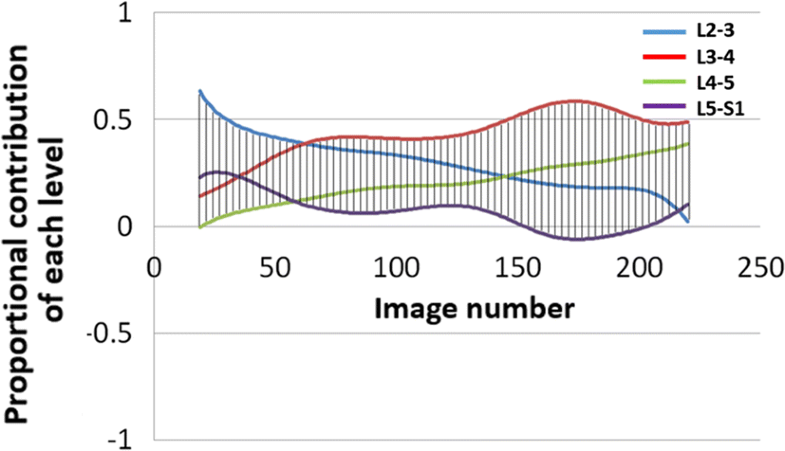

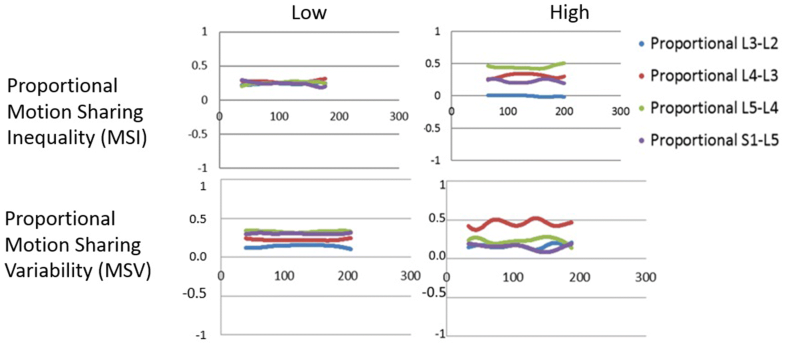

As most back pain has come to be regarded as mechanical and related to function, back motion studies have been central in the search for functional biomarkers [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Here, intervertebral motion data provide more intrinsic information than surface studies and data from fluoroscopic sequences have been found to differentiate groups of patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain (CNSLBP) from healthy controls by virtue of the patterns of segmental motion [10, 11]. Discriminating variables have been identified as intervertebral laxity (measured as the rate of displacement of a vertebra from its neutral position) and the motion sharing inequality and variability during passive flexion (MSI and MSV) [10, 11, 12].

Laxity denotes a loss of restraint in the mid-range [13]. It is an indicator of increased neutral zone length and may or may not be accompanied by increased range of intervertebral motion [14]. Motion sharing inequality (MSI) means an increased average difference between the segment that accepts the least proportion of the motion during the bending sequence and that which accepts the most [11]. This may be caused by stiffness at one or more levels, with or without hypermobility and/or mid-range laxity at others. Motion sharing variability (MSV), on the other hand, refers to erratic motion of individual vertebrae during the sequence [11]. (The numerical derivations of MSI and MSV are described in “Methods” and Supplementary material.) Recent studies using MSI and MSV [11] have tended to support relationships between CNSLBP and the integrated dynamic function of spinal motion segments hypothesised in the 1990s [13, 15]. Sagittal translation (or sliding as opposed to tilting motion) is typically also measured when instability is suspected—especially in patients with spondylolisthesis, but there is little evidence that it plays a role in CNSLBP [16].

Studies that measure multi-segmental continuous motion distribution in vivo are rare, it being traditional to measure motion individually at single levels quasi-statically, either using finite element (FE) modelling or laboratory specimens [17, 18]. However, in vivo individualised, dynamic, multi-segmental studies are needed for the clinical validation of both laboratory and FE modelling outputs and to investigate relationships between spinal mechanics and clinical outcomes [19, 20, 21].

Although intervertebral laxity and motion co-ordination have been investigated in CNSLBP, they have never been measured in treatment-resistant populations whose back pain is thought to be substantially mechanical in nature, yet this is where such investigations are more likely to be requested. A recent study found that lumbar intervertebral motion sharing (L2–S1) was correlated with the overall degree of disc degeneration in patients with CNSLBP, but not in controls [11]. However, patients with structural defects such as spondylolisthesis, or a history of invasive therapeutic procedures, such as surgery, were excluded from these studies. As patients with treatment-resistant back pain are probably more likely to have received surgical or other invasive interventions, it is necessary to assess the intervertebral kinematics in this population.

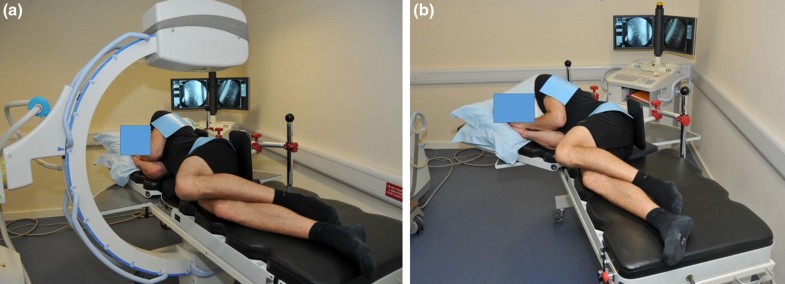

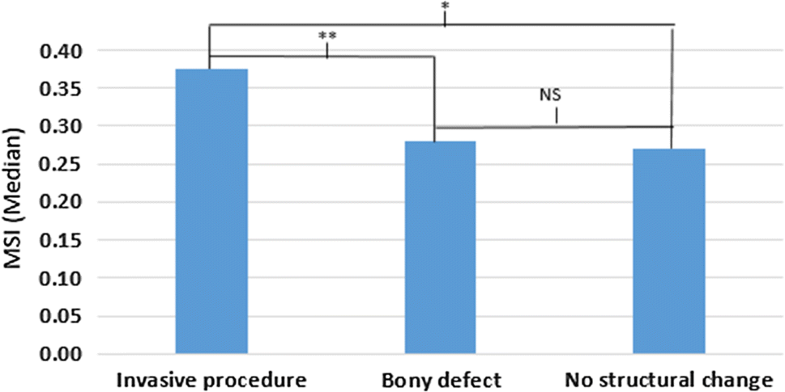

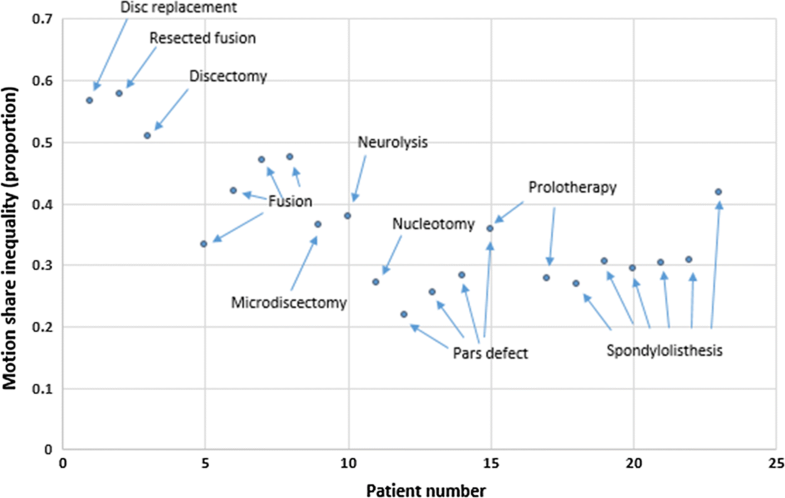

The aim of the present study was to investigate the degree of intervertebral laxity, MSI, MSV and sagittal translation during passive recumbent lumbar flexion and return motion in the lumbar spines of CNSLBP patients whose pain had failed to respond to treatment. Patients who had bony defects, invasive treatments and conservative care were included in the study. The main hypothesis was that these patients would have greater evidence of aberrant lumbar motion than pain-free healthy controls and that patients with bony disruption or a history of spinal surgery would have greater intervertebral motion dysfunction than those without.