Tania Gardner, BAppSc; Kathryn Refshauge, OAM, FAHMS DipPhty, GradDipManipTher, MBiomedE, PhD; James McAuley, PhD; Stephen Goodall, PhD, BSc, MSc; Markus Hübscher, PhD; Lorraine Smith, BA (Hons), PhD

Study Design. A prospective, single-arm, pre-postintervention study.

Objective. The aim of this study was to test the preliminary effectiveness of a patient-led goal-setting intervention on improving disability and pain in chronic low back pain.

Summary of Background Data. An effective intervention for the treatment of chronic low back pain remains elusive despite extensive research into the area.

An intervention using patient-centered goal setting to drive intervention strategies and encourage self-management for patients suffering chronic low back was developed.

Methods. A single group longitudinal cohort pilot study was conducted. Twenty participants (male = nine) experiencing chronic low back pain were involved in a patient-led goal-setting intervention, facilitated by a physiotherapist over a 2-month period with two monthly follow-up sessions after treatment conclusion. Participants, guided by the therapist, identified problem areas of personal importance, defined goals, and developed evidence-based strategies to achieve the goals. Participants implemented the strategies independently between sessions. Primary outcome measures of disability and pain intensity were measured at baseline, 2, and 4 months. Secondary measures of quality of life, stress and anxiety, self-efficacy, and fear of movement were also taken.

Results. Significant improvements (repeated analysis of variance P < 0.05) were seen in measures of disability, pain, fear avoidance, quality of life, and self-efficacy over the period of intervention and were maintained for a further 2 months after treatment conclusion.

Conclusion. This intervention is novel because the goals set are based on patients' personal preferences, and not on treatment guidelines. Our findings confirm that a patient-centered goal-setting intervention is a potentially effective intervention for the management of chronic low back pain showing significant improvements in both quality of life and pain intensity.

Level of Evidence: 4

Prevalence of chronic low back pain (CLBP) is high (9.17%), and despite evidence of treatment efficacy, there is continuing uncertainty regarding the clinical significance of most interventions.[1–5] The nature of CLBP is of heterogeneous, persistent and recurrent symptoms resulting in an array of bio-psychosocial problems that need to be managed long term.[6] Active patient participation in the self-management of health conditions is effective for improving quality of life, functional status, and health service use.[7]Self-management enables participants to make informed choices, adopt new perspectives, and gain generic skills that can be applied to new problems as they arise, to practise new health behaviors, and maintain or regain emotional stability.[8]

Patients' engagement in self-management also improves when their personal needs, concerns, beliefs, and goals are focused on, rather than the needs of the systems or professionals.[9] Patients and physicians often have differing preferences for treatment choices, based on the different values they place on outcomes.[10] Patients who are assisted to identify the problems and goals that are important to them can make more effective health care decisions, achieve a greater sense of personal control over their health, and engage in concordant dialog with their health professionals.[11]

Knowledge can be drawn from research into motivation and goal pursuit to inform and optimize self-management in CLBP. Self-determination theory of motivation proposes that an individual's motivation is enhanced if the goal meets the intrinsic needs of the individual.[12] Aligned with this, self-efficacy theory proposes that a person's perceived competence will determine whether that behavior will be initiated and the degree of motivation in maintaining that behavior, irrespective of obstacles.[13]

Goal setting is a component common of self-management programs and aims to facilitate behavior change to attain a desired outcome. Self-determination and self-efficacy are central to the mechanism behind goal setting.[14] Using a goal-oriented approach, patients identify problem areas of personal relevance in relation to their condition, establish goals they wish to achieve, and strategies to achieve them. This goal-setting process can be assisted and supported by the health care professional (HCP); however, the patient is encouraged to independently undertake the steps toward goal achievement and increase their sense of mastery and ownership in the goal-setting skills.

A systematic review investigating goal setting in rehabilitation, including CLBP, provides insight into the complexity of goal setting and the lack of a consistent approach, making it difficult to judge the true contribution of goal setting.[15] The degree of patient involvement in a goal-setting task often remains unclear with most studies describing goals to be set in collaboration with the therapist.[15] Goals in CLBP are most often set around activity-based or functional goals; however, these are not necessarily aligned with the patient's own needs or priorities.[16]

Goal setting is effective in facilitating self-management in several chronic conditions such as asthma,[14]diabetes,[17] heart disease,[18] and obesity.[19] However, little is found in the literature on the role and effectiveness of a patient-led goal-setting intervention in CLBP.

The present study aims to explore the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of an intervention using patient-led goal setting to drive the intervention strategies and facilitate self- management for patients experiencing CLBP. This approach differs from those described in the literature in that the patient's participation in setting the goal is clearly defined and it is the patient who solely sets the goal. The therapist guides the patient in developing evidence based strategies, and the patient implements these strategies independently.

We designed and modified a patient-led intervention consisting of education and goal setting. We recruited participants with CLBP, trialed the intervention, and followed participants for 4 months.

Inclusion Criteria. Participants were aged 18 to 65 years, with a history of nonspecific low back pain with a minimum duration of 3 months, reported pain of at least 4 on 10 cm Numerical Rating Scale, and disability of at least 20 points on the Quebec Back Pain Disability scale. These criteria reflect those of the general population of people with CLBP and enable finding change of a clinically worthwhile magnitude.

Exclusion Criteria. The exclusion criteria comprised inability to comprehend written English, recent lumbar spine surgery, or signs and symptoms indicative of serious pathology, such as bowel or bladder dysfunction, change in sensation in the perineal region, worsening pain at night, recent fevers/illness, or recent worsening of neurological symptoms in the lower legs.

Participant Recruitment. Participants were recruited from advertisements placed in university staff and student news bulletins as well as in a major hospital physiotherapy outpatients department.

Therapist Training. A comprehensive training session was conducted, before participant recruitment, by one of the authors (LS) to ensure that the research therapist was highly skilled in patient-led goal setting.

Study Design. We conducted a prospective, single-arm, pre-post trial with participants acting as their own control.

Intervention Procedure. The initial study procedure consisted of five sessions, each one conducted every 2 weeks with the therapist, followed by two monthly follow-up sessions (Table 1). At the initial session, participants were given a "Participant Handbook" comprising background information on the chronic pain model,[20] tips for self-management of CLBP, information on setting goals, and guidelines following the SMART model.[21]

The therapist took an initial history of the participant's back pain and discussed problems they experienced. The participant was asked to prioritize their problems according to what they wanted to work on. Evidence-based strategies were then discussed and the participant-set specific goals and strategies to work on independently between sessions. Participants recorded their identified goals, progress toward achieving these goals, any barriers, and agreed strategies to be undertaken toward goal achievement in their workbook.

Modified Intervention Procedure. During the initial pilot recruitment phase (N = 6), a high dropout rate (67%) was experienced and the design of the intervention was reviewed. Session 1 was modified by moving information about the chronic pain model to the second session. Participants were instead asked to read the participant handbook and to watch an audio-visual videoclip (https://youtu.be/C_3phB93rvI), both of which provided information on chronic pain. The chronic pain model was explained and discussed in session 2. A new cohort of 20 participants was recruited. After changing the intervention, a lower dropout rate (14%) was observed.

Primary Outcomes. Disability: The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS)[22] (minimum disability score = 20, maximum disability score = 100) was used to assess self-reported disability and is a reliable, valid, and sensitive measure to change functional disability.[23]

Pain Intensity. Pain intensity was measured using numerical rating scale (NRS) with anchors 0 and 10 (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain imaginable). The NRS is a well-established measurement tool,[24] and is a valid measure and responsive to changes.[25,26]

A minimally clinically worthwhile effect was considered to be a change of 20 points on the QBPDS and a change of 2 points on the NRS. A 30% improvement has also been suggested as a useful threshold for identifying clinically meaningful improvement on these measures.[27]

Quality of life was assessed using the SF-36 (minimum quality of life score = 0, maximum quality of life score = 100) with physical and mental component scores calculated.[28] The SF-36 is a validated multipurpose, short-form health survey with 36 questions, and is the most widely used measure of general health.

Negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress were assessed using The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS).[29] The DASS is a validated 21-item questionnaire that yields three subscale scores: depression (normal = 0–9, mild = 10–13, moderate = 14–20, severe = 21–27, extremely severe = 28+), anxiety (normal = 0–7, mild = 8–9, moderate = 10–14, severe = 15–19, extremely severe = 20+), and stress (normal = 0–14, mild = 15–18, moderate = 19–25, severe = 26–33, extremely severe = 34+). All of these are factors known to be associated with back pain.

Self-efficacy was assessed using the validated Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ)[30] (low self-efficacy score = 0, high self-efficacy score = 60). This is a self-report, 10-item questionnaire, where a higher score reflects greater self-efficacy.

Fear of movement/(re)injury was assessed using the validated Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK)[31](low fear of movement score = 17, maximum fear of movement score = 68). The TSK is a self-report 17-item questionnaire, where a higher score reflects greater fear of re-injury due to movement.

Demographic characteristics such as age, sex, level of education, and employment status were collected at baseline.

Treatment credibility was also measured because patients' initial expectations about the success of treatment are shown to affect the final treatment outcome.[32] A treatment credibility questionnaire was administered following the initial session, at completion of intervention at 2 and 4 months. This comprised four questions; (1) Confidence in the treatment relieving their pain, (2) Confidence in the treatment helping to manage their pain, (3) Confidence in recommending the treatment to a friend with a similar complaint, and (4) Logic of the treatment. Participants respond to each question on a seven-point Likert scale (0 = not confident at all, 6 = absolutely confident). The maximum score was 24, with a higher score indicating higher credibility.

Participant Goals. The type of goals the participants set were thematically coded and categorized by two investigators and domain themes established. To gauge the immediate effect of the goal-setting intervention, goal achievement was measured at the conclusion of the intervention at 2 months.

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Sydney and the St Vincent's Hospital Human Research and Ethics Committees. All participants gave written informed consent.

This was an exploratory study to investigate the feasibility and possible impact of the intervention, and participants acted as their own control. A pre-specified sample size of 20 (completed) was chosen. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Mauchly tests were conducted to confirm sphericity. We compared within-group differences over time in outcomes at baseline, 2, and 4 months. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the effect of the intervention over time from baseline, 2 months (end of intervention), and 4 months (2 months postintervention) on measures of disability, pain intensity, quality of life, self-efficacy, fear avoidance, depression, anxiety, and stress. Single-sample paired t tests were used to make comparisons at 2 and at 4 months. A P value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance for all analyses.

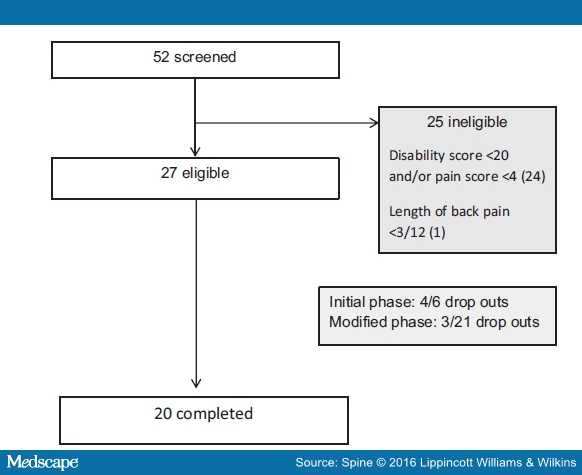

We recruited 20 participants (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of study participants are reported in Table 2. Our sample was consistent with normative data of patients with CLBP for gender, age, duration of pain, and pain intensity.[33]

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participant recruitment process.

We found improvements over time for most measures as well as mean change from baseline to 2 months (Table 3). Disability, pain intensity, quality of life, self-efficacy, fear avoidance, anxiety, and stress all improved significantly over time (P < 0.05). The change in depression scores was nonsignificant (P = 0.78). Disability, pain intensity, physical quality of life, mental quality of life, total quality of life, self-efficacy, and fear avoidance measures improved significantly between baseline and 2 months (P < 0.05). Nonsignificant changes occurred in depression, anxiety, and stress (P > 0.05), from baseline to 2 months. Improvement in disability, pain intensity, physical quality of life, mental quality of life, total quality of life, self-efficacy, fear avoidance, and anxiety measures remained significantly better at 4 months than baseline and similar to the 2-month scores (P > 0.05).

The participants set a total of 63 new goals. This represented an average of 3.2 goals per participant.

Thematic analysis of the goals identified five domains. The most common domain related to physical activity (49.2% of goals), followed by workplace tolerance (14.3% of goals), coping skills (11.1% of goals), relationships (6.4% of goals), and sleep/energy (6.4% of goals). Seventeen participants set goals in more than one domain, for example, exercise and sleep, workplace tolerance, and coping skills. Table 4 provides examples of the participants' goals and strategies developed.

Due to missing data, only 52 of 63 goals were included in the goal attainment results at 2 months. From the total number of goals (N = 52), a majority of goals (77%) were rated as "working toward" or above, and 13.5% rated as achieved (Table 5).

This pilot study found that a reduction in pain and disability was observed in patients who took part in an individualized patient-led goal-setting intervention. These improvements were sustained for 2 months following intervention. Whether our model of intervention was associated with these improvements should be investigated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). This novel intervention has not previously been tested for CLBP.

This was a proof-of-concept study; therefore, the lack of a control group for comparison of effect limits any solid inferences about potential treatment effect. However, we believe that the within-group changes in improvement are larger than would be expected because of temporal effects, given the chronicity of symptoms before entry to the study. In a systematic review investigating the pattern of symptom improvement within intervention groups in nonspecific CLBP, it was suggested that a within-group standardized mean difference of 0.83 [95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.65–1.07] would be expected in pain intensity at 6 weeks follow-up, regardless of which treatment arm was tested.[34] In our study, the mean differences in outcomes exceeded the expected standard pattern of improvement.

The most surprising finding was the significant improvement in pain. In chronic pain conditions, pain is not expected to improve, particularly with an approach that aims to change behaviour.[35] Little or no difference has been found for pain relief or function between cognitive therapy and waiting list groups.[2]No significant change in pain intensity has been found with a combination of cognitive therapy with either education or physiotherapy compared to education or physiotherapy alone.[2]

Systematic reviews that investigated various forms of patient education for chronic back pain have found limited success for improving pain and function.[36,37] In contrast, our intervention combined improving health literacy with participants setting their own goals. Interestingly, providing the education material as homework and delaying the discussion of the education content resulted in a significant reduction in the drop-out rate. This new approach may have allowed participants to process the information and reach a closer point of acceptance of their pain, changing their perception of the pain, and leading to re-engagement with activities. The education component in combination with patient-led goal setting was a useful strategy to underpin these active cognitive and behavioral strategies.[37] By reconceptualizing pain, patients may become more responsive to strategies such as re-engagement with movement and cognitive reframing.[38]

The study has several limitations. The population used to recruit participants was predominantly from the community and noncare seeking, were high functioning in terms of employment, social, and recreational activity, and on low levels of medication. This may not reflect the population from a primary care setting. Participants were volunteers, suggesting a high level of motivation to participate in goal setting, adherence to chosen strategies, and behavior change, which may not be representative of a clinical population. The fact that one researcher conducted the intervention may be a source of bias, as the delivery of the intervention may not be as uniform or as successful with other clinicians. Due to the small sample size, solid inferences about the results cannot be drawn from this pilot study.

Treatment credibility scores were high (18.6/24 at baseline, 18.1/24 at 4 months) reflecting high expectations of the intervention by participants. Higher treatment expectations are associated with higher functional improvement in acute low back pain[39] and have been shown to be directly linked to health beliefs, self-efficacy, locus of control, and attitudes.[40] Despite the likely high motivation among participants volunteering for a study, the high credibility score was surprising in view of the numerous studies that have consistently shown that patients with low back pain expect a clear diagnosis, pain relief, and physical examination as part of their care,[41] none of which were part of this intervention. The low rate of completion of goals (13.5%) may reflect the nature of goals chosen and the limited time of 2 months to achieve them. The goals may also have been influenced by the length of CLBP experienced by the participant. Current CLBP guidelines cite the need for a biopsychosocial approach,[42,43] yet ongoing professional education and current practice remains bio-medically focussed.[44] The change to a more biopsychosocial approach may be a source of resistance among HCPs.[45] Such a shift in the approach to CLBP treatment will require development of professional training, undergraduate training, and a reconceptualization of the approach to chronic pain management and the role played by both patients and HCPs.

Patient-led goal setting is a promising and feasible approach in the management of CLBP. Preliminary results suggest that the model of patient-led goal setting has the potential for improving disability, pain, quality of life, pain, self-efficacy, and fear avoidance beliefs. Larger investigations involving randomized controlled trials are warranted to assess the wider use of this model and further understand this approach in CLBP.

C/ San Pedro de Mezonzo nº 39-41

15701 – Santiago de Compostela

Teléfono: +34 986 417 374

Email: secretaria@sogacot.org

Coordinador del Portal y Responsable de Contenidos: Dr. Alejandro González- Carreró Sixto